Happy Birthday to one of my favorite people!! Filly, you’re one of a kind. Quick to help, fun to talk to, and no one can make me laugh like you do!! I love you!!

Happy Birthday to one of my favorite people!! Filly, you’re one of a kind. Quick to help, fun to talk to, and no one can make me laugh like you do!! I love you!!

Quisley’s Castle is an unusual home in Eureka Springs, Arkansas.

From the Quisley’s Castle website:

My great grandmother’s maiden name was Elise Fioravanti (1910-1984). She was part Italian. She came to the Ozarks when she was nine. She loved the outdoors and began to collect rocks as she walked along a creek bed to school. When she was 18, during the depression, she married my great grandfather, Albert Quigley (1905-1972). He was the type of fellow who brought her rock collection with them to the site of his farm and lumber mill. They lived in a lumber shack and had five children. My great grandfather promised her a house with the lumber cut off their own property.

They argued about it for several months. As soon as Albert headed for work at the lumber mill one June morning in 1943, Elise Quigley gathered their children around her and ordered “we’re going to tear down the house.” And demolish the family’s three room house they did. “when Bud came home that night, “Mrs. Quigley related, “he was living in a chicken house, where we’d moved all of our stuff.”

Mrs. Quigley had already designed her dream home. She wanted two things: Plenty of room for the robust family and a “home where I felt I was living in the world instead of in a box. I designed it in my mind, but I couldn’t tell anybody what I wanted, so I sat down with scissors, paste, cardboard and match sticks and made a model.”

The biggest obstacle was that the design which called for 28 huge windows. Mr. Quigley wanted to wait to build the house because glass was unavailable during the war, but now construction began immediately. Built entirely of lumber off their land and with their own labor, only $2000 in cash was spent on supplies and glass, which didn’t become available for three years. The family survived the winters by tacking up material over the holes in layers.

To bring nature indoors, four feet of earth was left bare between the edges of the living space and the walls. Into the soil, which borders the rooms on the inside, Mrs. Quigley planted flowering, tropical plants that grow up to the second story ceiling. The two remaining original plants are over 70 years old now.

Stones that Mrs. Quigley began collecting as a girl assumed an important part of the house. Working tenderly for three years, Mrs. Quigley covered the outside walls with a collection of fossils, crystals, arrowheads and stones selected from the creek beds for their beauty. A perennial garden surrounds the house.

The inside of the house is a collection of family antiques and mementoes that express Mrs. Quigley’s love of nature. Especially spectacular is the “Butterfly Wall” that is beyond imagination.

This was her home and passion for another 50 years as she continued to collect and surround herself with the nature she loved. My great grandparents were very compatible; he took her everywhere she wanted to collect, as she couldn’t drive. He continued to make a living with the farm and lumber mill until he passed away in 1972, at the age of 66. Elise Quigley died at the age of 74 in 1984

The Quigley home, without intention, became a favorite stopping place for people traveling through the Ozarks. Now after seventy years, the Quigley’s great granddaughter still welcomes guests into the family home.

The Arizona State Tree, Palo Verde, holds a significant place in Arizona’s identity as an official state symbol. Designated as the Arizona State Tree by legislative action, the Palo Verde stands out for its botanical significance and distinctive features.

Known for its vibrant green bark and beautiful yellow flowers, the Palo Verde tree is deeply intertwined with the Sonoran Desert landscape. Its ability to thrive in arid conditions, with its unique ability to conduct photosynthesis through its green bark, symbolizes resilience and adaptation. This tree not only beautifies the Arizona landscape but also plays a crucial role in supporting the desert ecosystem by providing shade, shelter, and sustenance for various wildlife species. The Palo Verde tree is a testament to Arizona’s commitment to preserving its natural heritage and the delicate balance of its environment.

The Palo Verde was chosen as the official state tree of Arizona due to its deep-rooted significance in the state’s history and culture. As a native tree to the desert landscape, the Palo Verde represents the essence of Arizona’s ecosystem and environmental importance.

Known for its unique green bark and vibrant yellow blossoms, the Palo Verde stands out in the arid landscape, offering not only a visual spectacle but also serving a vital role in providing shade during scorching summer days. As a drought-tolerant species, its presence helps in conserving water in the region’s delicate ecosystem. The tree supports various wildlife species, from birds to insects, creating a diverse habitat that contributes to the overall biodiversity of the state.

The Andean cock-of-the-rock is the national bird of Peru and the male and female are visually distinct. The male has a striking bright red head with a large crest which wraps around over the beak. Both males and females have the crest though it is larger on the males. Males also have red breast feathers. Down the back the wings and tail are black with a large white patch in the center of the upper side. These wings are wide and strong to provide maneuverability to move through the forest. Their wingspan is 23.6-25.6in across. Females are much duller in color. Their feathers are a greenish or olive-brown color across their entire body.

Both genders have a short bill with a hooked shape. Males are slightly larger than the females. On average an Andean cock-of-the-rock will measure 12-12.5in long and weigh 7-9.5oz.

The Andean cock-of-the-rock is an omnivore. Their diet includes a range of fruits, berries and insects. Small vertebrates may also be eaten on occasion. They perform an important role in dispersing seeds from fruits they eat through the forest.

South America is the native home of the Andean cock-of-the-rock. Here they can be found throughout Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. As their name suggests they live in parts of the Andes Mountain range.

They make their home in forests and wetlands. In addition to these they can be found in rocky gorges and ravines on the borders of rivers and streams. This habitat led to the rock portion of their name.

Breeding occurs from February to July though this can vary across parts of their range. Males will gather at a location known as a lek. Here up to 15 males will compete for the mating rights of a single family. A number of males will glare at one another before one dips its head and lets out their raucous call. The others begin to join before a display of wing-flapping and head bouncing occurs. Females may approach the males throughout and their displays intensify at this point. Young males will participate in the lek before sexual maturity to try and learn the ways to be successful.

Once a female selects the male she would like to mate with she will walk behind him and nibble at his feathers or peck his neck. Males will return to the lek after mating and try to attract another a mate. Females create a nest from mud, palm fiber and saliva which is shaped like a cup. This is built against a rock or in a cave. It may take a month for her to perfect her nest and she will not mate till this is complete.

Following a successful mating the female will deposit two eggs in the nest which she incubates alone for their 22-28 day incubation. One clutch is produced each year. At hatching the chicks are highly underdeveloped and the mother provides them with food. They require care for the next 45 days.

If you’re planning a trip to California, here are some “must-see” paces!

Alcatraz Island was once the most secure federal prison in the U.S., and held notorious inmates like Al Capone. After being decommissioned in 1963, the prison is now a museum, welcoming millions of curious travelers every year. Catch the ferry on Pier 33 to Alcatraz and explore the island at your own pace as you soak up the views of San Francisco and the bay. You can take a guided tour with a park ranger to learn more about the intriguing anecdotes about the facility’s fascinating history.

The San Diego Zoo pioneered cageless exhibits and offers travelers a fun and informative experience. Featuring over 4000 animals, the park gives you a peek into the wildlife of several ecosystems, from deserts to rainforests. Ride the tour bus, which crosses three quarters of the zoo’s area, and learn more about the animals from the guide as you view them in their natural habitats. You can also hop on the Skyfari gondola lift to see the entire park from above.

Get ready for the ultimate Hollywood experience! Find a full day of action-packed entertainment all in one place: thrilling theme park rides and shows, a real working movie studio, and Los Angeles’ best shops, restaurants and cinemas at CityWalk. Universal Studios Hollywood is a unique experience that’s fun for the whole family. Explore Universal Studios backlot on the legendary Studio Tour. Then face the action head on in heart-pounding rides, shows and attractions that put you inside some of the world’s biggest movies.

A public observatory in Los Angeles, Griffith Observatory has been featured in many movies, from ‘Rebel Without a Cause’ to ‘La La Land’. Nestled on Mount Hollywood, Griffith Observatory boasts some of the best views of the city—the best time to visit is at sunset. Inside, the observatory offers quite the experience as well—it has a planetarium, various exhibits, free-to-use telescopes, and more. The best part? Admission is free and it’s easily accessible with plenty of parking.

At La Jolla Cove surrounded by sandstone cliffs on the San Diego coast, the water is calm enough for travelers to enjoy diving and snorkeling. Walk along the rocky shore to spot large colonies of sea lions lounging in their natural habitat and looking after their pups, and have a picnic while soaking up the views of the ocean from the cliffs at sunset. If you visit at low tide, you’ll get to swim in the crystal clear tidal pools as well. You can also visit Sunny Jim’s Sea Cave which is accessible via a tunnel.

Located in downtown San Diego, the USS Midway (Museum) was America’s longest-serving aircraft carrier of the 20th century. Today, the interactive museum is an unforgettable adventure for the entire family as guests walk in the footsteps of the 225,000 young men who served on Midway. Visitors explore a floating city at sea, the amazing flight deck and its 29 restored aircraft, flight simulators, and are inspired in the Battle of Midway Theater, included with admission.

SOURCE: TRIPADVISOR

Today is Erma Bombeck’s birthday (born in 1927 and passed in 1996) and I wanted to bring some of my favorite Erma-isms.

I found a recipe for a new dessert–Peanut Butter Brownies!

Ingredients

1 1/2 cups creamy peanut butter

1/2 cup all-purpose flour

2/3 cup unsweetened cocoa powder

3/4 cup salted butter

3 oz. dark chocolate bar (72%), chopped

1 1/4 cups granulated sugar

1/4 tsp. kosher salt

1 1/2 tsp. vanilla

3 large eggs

1/3 cup semisweet chocolate chips

1/3 cup peanut butter chips

Directions

Preheat the oven to 350°. Lightly grease a 9-by-9-inch square baking pan then line with parchment paper, leaving an overhang on all sides. Microwave the peanut butter for 30 seconds; stir. Repeat as necessary until peanut butter is pourable. Pour into the prepared pan. Freeze until firm, about 1 hour. Remove the peanut butter layer and transfer to a small sheet tray. Store in the freezer until ready to use.

Sift together the flour and cocoa powder in a medium mixing bowl.

Melt the butter and chocolate in a medium saucepan over medium heat, stirring often. Remove from heat.

Beat the sugar, salt, vanilla, and eggs in a large bowl with an electric mixer at medium-high speed until fluffy, about 3 minutes. Slowly drizzle in the melted chocolate mixture on low speed until combined. Beat in the flour mixture on low speed until just combined.

Pour half of the batter into the prepared pan. Remove peanut butter layer from the freezer, and place on top of brownie batter. Top with the remaining half of the brownie batter, and spread to even out the top. Sprinkle the top with the chocolate chips and peanut butter chips.

Bake in the preheated oven for about 40 minutes or until puffed, dry to the touch, and set on the top (a wooden pick inserted in the center will not come out clean). Cool completely in the pan on a wire rack, about 3 hours. Cut into 16 squares.

Enjoy!

Today is John Travolta’s birthday (born in 1954), and I found an article on life-mag.net detailing some interesting tidbits about this amazing man!

1 He met his late wife, Kelly Preston, on the set of the 1989 film, The Experts:

At the time, Preston was married to actor Kevin Gage. But that didn’t stop their love as they got together after her divorce. They ended up getting engaged in 1991 in Switzerland and welcomed three children. Kelly sadly passed away in 2020 after a private battle with breast cancer. “It is with a very heavy heart that I inform you that my beautiful wife Kelly has lost her two-year battle with breast cancer. She fought a courageous fight with the love and support of so many,” Travolta shared on Instagram.

2 He’s still super close to his Grease co-star, Olivia Newton-John:

The pair first met on the 1978 musical film. “We were together not that long ago, about three months ago, and we text each other all the time,” he told Us Weekly in 2019.

3 When Olivia was diagnosed with breast cancer, he praised her for her strength:

“She’s doing great,” John told Us Weekly at the premiere of The Fanatic. “And she looks fantastic! I’m so proud of her … she’s pulling it off like I’ve never seen anybody [do].”

4 He turned down the starring role in Forrest Gump:

Tom Hanks went on to win his second Oscar for the role. Even so, John doesn’t regret turning it down. “If I didn’t do something Tom Hanks did, then I did something else that was equally interesting or fun,” he told MTV in 2007.

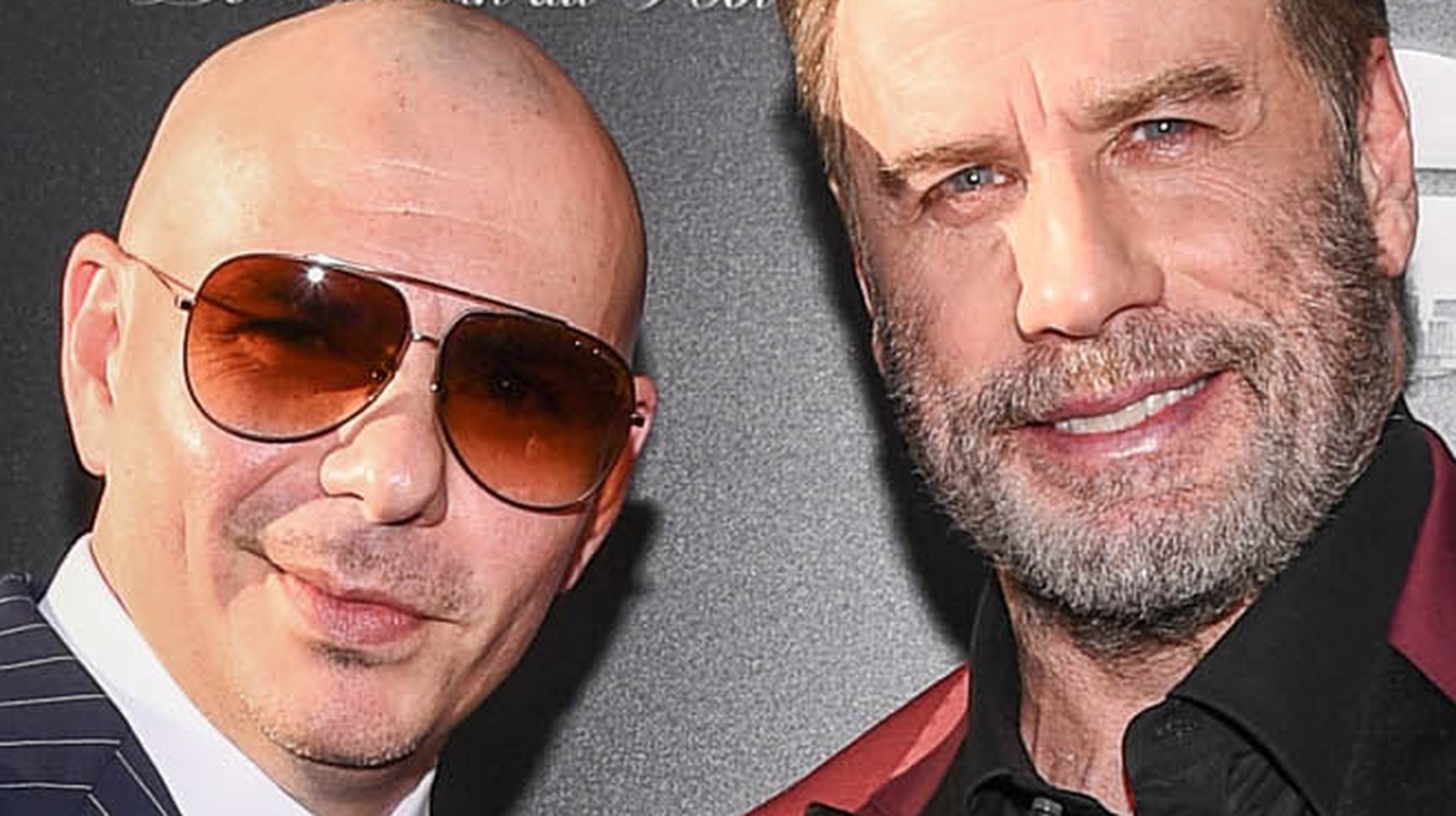

5 He was once in a Pitbull music video:

If Saturday Night Fever taught us anything, it’s that Travolta never shies away from a dance floor. He appeared in the music video for “3 To Tango.” You don’t realize that it’s him until the end thanks to the bald head.

6 He had the “most despicable moment” in his acting career on The People v O.J. Simpson:

He told Parade that it was the scene where his character blackmailed Robert Kardashian. “I can’t believe that the character actually leverages him to try to settle, to convince the team to settle. It was such a strange day to play that and I want to see how that came out.”

7 Starring in a Western film was on his bucket list:

He managed to tick that off when he starred in In the Valley of Violence. “I think you have to do at least one Western, and it’s harder to do genre pieces today,” he told Slash Film. “Urban Cowboy was sort of a modern Western, but an old-fashioned one was what I really wanted to try,” he continued. “And I so preferred what I was given to do in that—this legless, crotchety old marshall—it was so much more fun.”

8 He’s a licensed pilot:

He owns several planes and often flies his family around. But he once had a terrifying near-death accident when his plane experienced a total electrical failure. Thankfully, he was able to make an emergency landing.

9 His favorite movie role was on A Civil Action:

The reason why? “I really get a kick out of good writing,” he told The Consequence of Sound. He said that as soon as he saw the script for one of the scenes in the film, he “couldn’t wait to do this.”

10 He’s had some wild fan encounters:

Unfortunately, some of these mirror the obsessed fan he plays in The Fanatic. One time, a stranger entered his home. “We were having our Sunday afternoon and you’re like, ‘Who is this?’”

11 He’s the one who picked Olivia for the role of Sandy in Grease:

This is something that he takes immense pride in. “She’s got a huge soul,” he told Extra. “She is an eternal love for me and will always be… and I picked her. I take the pride of having picked Olivia Newton-John for ‘Grease.’”

12 He felt terrible for butchering Idina Menzel’s name at the Oscars:

Sooo many memes were created that day, but Travolta wasn’t laughing. “I’ve been beating myself up all day,” he said in a statement to E! News. Thankfully, he had some words of wisdom from Idina Adele Dazeem . “Then I thought…What would Idina Menzel say? She’d say, ‘Let it go, let it go!’” he said. “Idina is incredibly talented and I am so happy Frozen took home two Oscars Sunday night!” Thankfully, Idina laughed the incident off and even got her revenge.

13 He sang a duet alongside Miley Cyrus:

We never thought we’d see these two in a sentence together, much less a song, but here we are! The duo sang “I Thought I Lost You” on the 2009 soundtrack for the animated movie, Bolt .

14 Pitbull inspired him to shave his head:

If you’re wondering why he’s been rocking a bald head for years now, this is it: “I did a movie called From Paris, With Love where I shaved it. So I got used to it, some people got used to it,” he said on Jimmy Kimmel Live. “I became friends with Pitbull, and I loved how it [looked.] All us guys gotta stick together that do this.” He suits the look so more power to him!

15 He and Olivia once recreated their signature Grease looks:

It’s been 40 years since Grease came out but who can tell from looking at this picture? They had dressed up as their characters for special screenings of the film.

16 He never officially finished school.

“Not too many of my friends identified with what I was doing,” he told The Phoenix. “I participated in football and basketball, and did what they were doing, but not many kids understood my going to acting studios at night.”

17 He didn’t use a stunt double for Urban Cowboy.

He had his own mechanical bull installed in his house before they filmed the movie that way he could get used to the feeling. By the time it came to film, he didn’t need a double!

18 He regrets turning down Chicago.

It’s one of the bigger losses of his professional life. “Probably the one I didn’t explore enough is Chicago. (Studio executive) Harvey Weinstein offered it to me three times,” he said to Entertainment Tonight. “I never met with the director because I thought the play was about a bunch of women who hated men, and I like women who like men.” Even Hugh Jackman was offered the role, but ultimately the role went to Richard Gere.

19 Marlon Brando and Travolta had a close relationship!

Travolta revealed to Us Weekly that Marlon Brando told him he’d laughed a lot when Travolta imitated him on Saturday Night Live in 1994. Brando also gave him advice in the past. “The best piece of advice I ever received was from Brando. He said, ‘Don’t expect things from people that they can’t give you,’” Travolta wrote. Which to be fair, is amazing advice. Hopefully, Travolta took it to heart as much as possible.

20 He’s not the best cook but he can make a mean cup of coffee.

“I don’t often cook, but if I do, I’d consider myself a decent cook. I wouldn’t embarrass you, and I’d make it flavorful.” he admitted in Us Weekly. “I wake up and have the strongest cup of coffee you could imagine using half a pound of Starbucks Sumatra blend. It’s epic.”

21 He also told *Us Weekly* where his favorite places to visit are:

“My top five places to fly are Sydney, Australia, because it’s so inviting; Shannon, Ireland, because it’s beautiful; Hong Kong, China, because it’s exotic; São Paulo, Brazil, because the approach is between the high-rises; and Paris, because of the Eiffel Tower.”

22 Princess Diana wore an iconic dress that was later named after him.

She once wore an iconic gown to the White House and it was there that she danced with John Travolta. The dance was so famous, and the dress so beautiful, and their relationship so wonderful, that the dress soon got the nickname: “Travolta dress”.

22 One of his greatest celebrity experiences was not with Mariah Carey.

Although it certainly makes for a fantastic picture! He admitted to Us Weekly, “I’ll never forget flying with Muhammad Ali from Los Angeles to Las Vegas.” That must have been one heck of a conversation.

SOURCE: LIFE-MAG.NET

Arkansas’s state motto is Regnat Populus, which is Latin for “the people rule.” No other state employs this motto, in either Latin or English, although South Dakota’s comes close: “Under God, the people rule.” The motto’s use is mostly limited to the Seal of State and its derivatives used by various state officers.

The constitution under the terms of which Arkansas entered statehood in 1836 stipulated that the governor must “keep” the Great Seal of the State. Its design, mentioned in Article 5, Section 12, should be “the present seal of the territory, until otherwise directed by the general assembly.” That seal bore, among other elements, the Latin motto Regnant Populi, which could be translated as “the people rule.” The origin of the phrase, either in Latin or English, is unknown. Its promoter was likely the recording clerk of the first territorial assembly, Samuel Calhoun Roane, who is usually credited with the initial design of the territorial seal. The 1864 Arkansas General Assembly reiterated the phrase’s place in the state seal while specifying an updated, if not simplified, design for the omnibus emblem.

In 1907, the General Assembly acted to modify the motto’s Latin form in order to better communicate a sense of its English version. “The people rule” had originally been rendered in Latin as regnant populi, employing the plural form of the noun, i.e., “the (or ‘some’) peoples,” implying multiple groups. An act approved by Acting Governor Xenophon O. Pindall on May 24, 1907, modified the subject to populus, signifying a single group, as in “the people.” Adjusting the verb to agree with the subject resulted in regnat populus, in which form the motto survives today.