11 What was the English sweating sickness?

Between 1485 and 1551, England suffered five outbreaks of a disease so virulent that it could kill an otherwise healthy person in a matter of hours. Its favorite targets seemed to be wealthy adult males; children and elderly people were generally spared, while the aristocracy, members of professional classes, and the clergy seemed particularly vulnerable. The epidemics were short-lived but brutal, and in all but at most a handful of instances the disease did not spread beyond England.

Symptoms came on quickly; according to one account it came with “a sudden great sweating and stinking with redness of the face and of all the body” along with fever, headaches, and delirium. As many as half of those afflicted died within 18 hours. Anyone who made it through the first day would probably recover, but there was always a chance of reinfection.

Whatever the disease was, it vanished as mysteriously as it appeared. The last outbreak was in 1551, and apart from some potential minor appearances in the following decades, we haven’t seen it since—though a similar affliction, known as the “Picardy sweat,” popped up in France a century and a half later, causing nearly 200 small outbreaks before it too disappeared in 1861.

Many theories have been floated over the centuries. It’s been suggested that the English sweating sickness could have been a strain of typhus or influenza, or even anthrax. A more likely answer emerged in 1993, when a similar outbreak occurred in the American Southwest. This disease was caused by a hantavirus, leading researchers to speculate that a hantavirus was also behind the English sweating sickness and the Picardy sweat. Since hantaviruses can be spread by rodents, this could explain why large households and academic institutions were hit so hard by the disease: Well-stocked kitchens and pantries would have attracted mice and rats, and household staff could have aerosolized the virus in their droppings while sweeping. This might be the best solution we get; according to a 2014 paper published in the journal Viruses, a conclusive answer will probably never come.

12 What were the Nazca Lines for?

The Nazca (or Nasca) Lines are an array of geoglyphs carved into the coastal plain of southern Peru. Some are simply straight lines running in all directions, while others depict animals or people.

The lines were studied by researchers traveling on foot in the 1920s, but it wasn’t until commercial pilots began flying over the area in the 1930s that their full scope and elaborate design was revealed. According to UNESCO, the Nazca Lines are “unmatched in [their] extent, magnitude, quantity, size, diversity and ancient tradition to any similar work in the world.” They were built over the course of 1000 years, mostly by removing darker stones to reveal the lighter colored sand underneath.

The question that still puzzles researchers is, why were the geoglyphs made? For decades, some archaeologists believed they served as giant astronomical calendars, possibly linked to constellations or other celestial bodies. Recent research suggests a more earthly purpose: It now appears that the Nazca Lines might have been connected to rituals meant to appeal to the gods for rain. It’s possible they marked processional routes used by pilgrims as they traveled to temples, or that rituals were performed at designated points along the lines themselves.

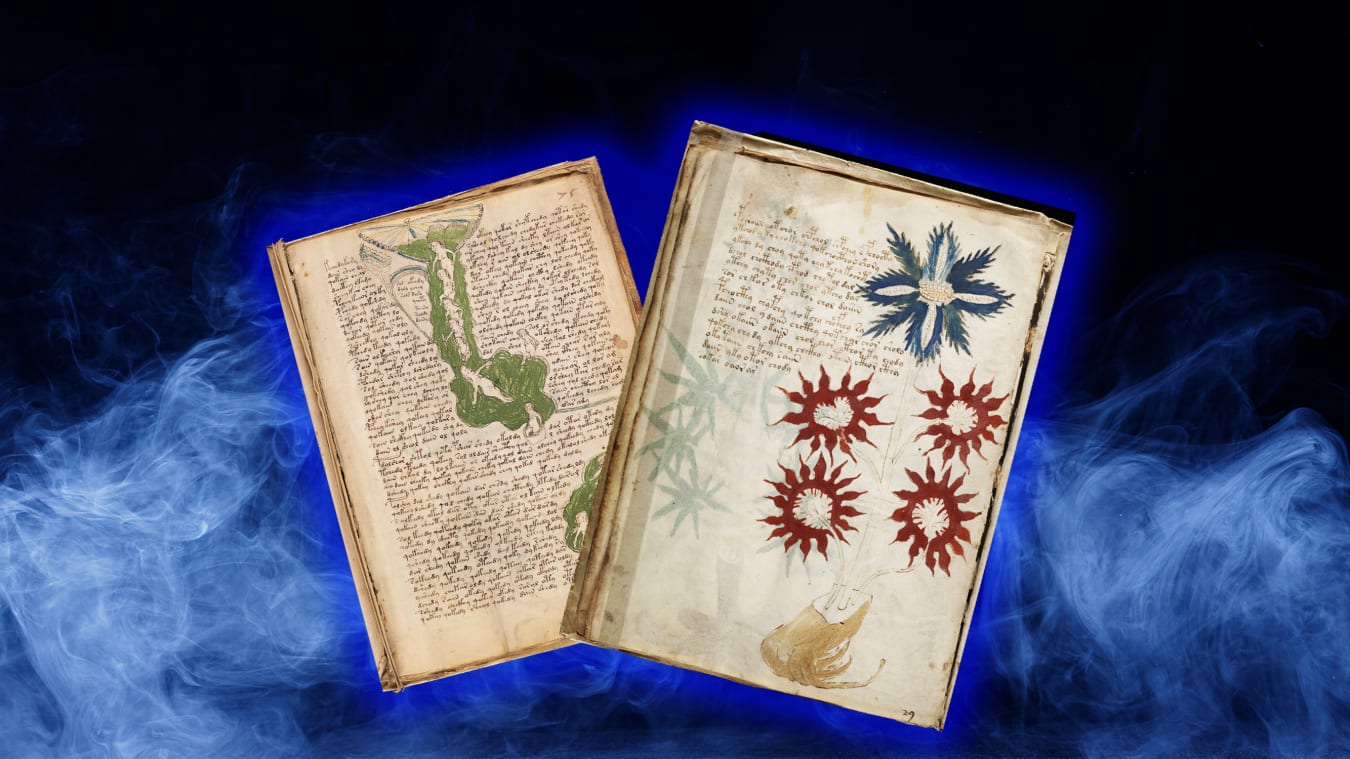

13 What does the Voynich Manuscript say?

We don’t know when, where, or by whom the Voynich Manuscript was written, but there’s an even larger mystery to solve: We have absolutely no idea what it even says. The text—which is accompanied by astrological charts, illustrations of strange plants and naked, possibly pregnant women emerging from tubes and funnels or wading in green fluid, and other bizarre images—is composed in a writing system that doesn’t appear on any other document or object we’ve discovered so far. Some, including the late U.S. Army cryptographer William Friedman, believe Voynich was written in a synthetic language. Others think the manuscript uses a dead language such as proto-Romance, a precursor of vulgar Latin (though that claim was highly controversial), or that it could be written in some form of code or cipher.

Whatever the case, the book is divided into six sections: one devoted to botanical studies; one that is apparently concerned with astrological and astronomical matters; one that contains elaborate (and super weird) biological drawings; a section containing what Yale University, the book’s keeper since 1969, identifies as “cosmological medallions”; a section dedicated to pharmaceutical sketches; and a text-only portion devoted to what appear to be recipes.

Since bookseller Wilfrid Voynich found the manuscript in 1912, secreted in a bundle of medieval manuscripts he’d purchased from a Jesuit college, the book and its complicated history have been obsessively studied and analyzed. Carbon dating tells us the manuscript’s vellum was sourced in the early 15th century; pigments are consistent with that date as well, so that’s presumably when it was written. We know (or at least we think we know) it’s been owned by a Holy Roman emperor, an alchemist, a famed Bohemian doctor, and possibly Elizabethan occultist and court astrologer John Dee. If any of its previous custodians figured out how to read it, they kept it to themselves, but you’re welcome to give it a go if you’re feeling froggy.

14 Who built Stonehenge?

Since the 17th century, the popular imagination has linked Stonehenge to the Druids, but the timeline doesn’t shake out—the earliest historical references to the Druids date to the 4th century BCE, while Stonehenge was most likely built sometime between 3000 and 2000 BCE. But if the Druids didn’t build it, who did?

There might not be one simple answer. Construction of Stonehenge is thought to have taken place in several phases over the course of about 1500 years. The first monument at Stonehenge simply consisted of a circular earthwork that enclosed dozens of pits and possibly some rocks. The iconic stone slabs were added a few hundred years later—around the same time the Egyptians were building the pyramids at Giza. It’s long been thought that Neolithic hunter-gatherers got the ball rolling, but new evidence suggests Stonehenge’s builders were the descendants of Mediterranean farmers who migrated to northwestern Europe 6000 years ago.

Whoever Stonehenge’s builders were, their accomplishments were astonishing. We’re still trying to figure out how Stonehenge was constructed; some of the stones came from nearby quarries, but others were sourced from a Welsh site 200 miles away. We have no idea how people who didn’t even have wheels were able to transport the stones and hoist them into place.

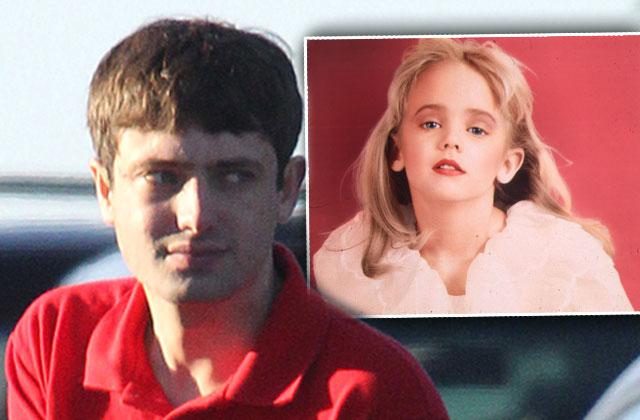

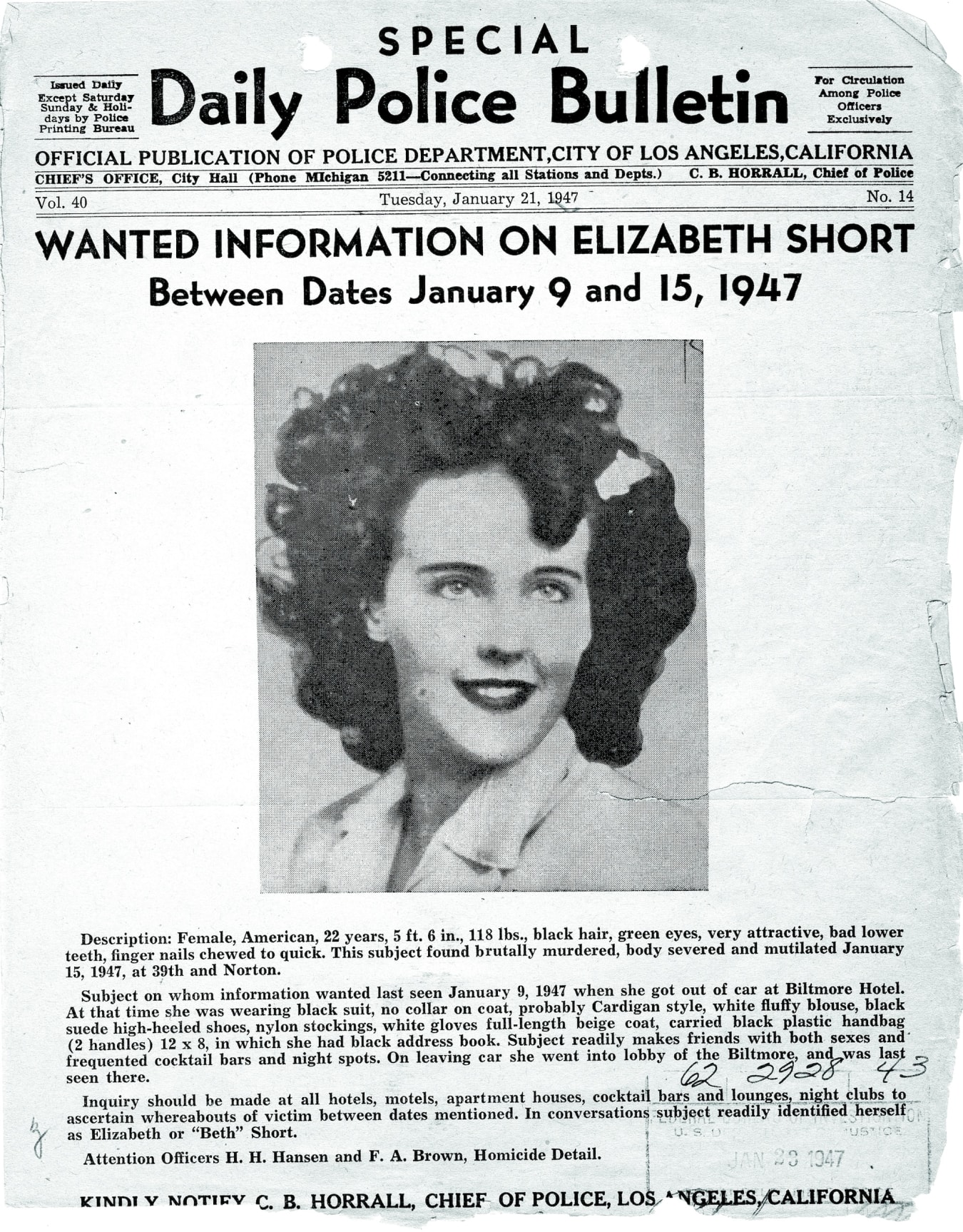

15 Who killed the Black Dahlia?

History is full of unsolved murders, from the disappearance and presumed assassinations of King Edward V and Prince Richard, Duke of York, in 1483 to the Zodiac killings that terrorized the Bay Area in the 1960s. But none has captivated American popular culture quite like the horrific murder of Elizabeth Short, the young woman who will forever be known by the sensational nickname given to her by the press: the Black Dahlia.

Short’s body was discovered on January 15, 1947, in a vacant lot in Los Angeles. The brutality that had been visited upon her, both pre- and post-mortem, is still shocking: Her face had been grotesquely disfigured, her body cut in half, and some of her organs removed, among other acts of torture and mutilation. No one was ever arrested for Short’s murder, and the case eventually went cold. Recent theories have blamed everyone from Orson Welles to Bugsy Siegel.

The Los Angeles Police Department investigated dozens of suspects, including George Hodel, a surgeon whose social circles included surrealist photographer Man Ray and The Maltese Falcon director John Huston. Upon learning his father had been investigated for the murder, George’s son, Steve, decided to clear his dad’s name after his dad’s death in 1999, only to become convinced that George was indeed Short’s killer. Steve published his findings in a well-received and fairly convincing 2003 book, but later lost some credibility when he also accused his father of being the Zodiac Killer.

In 2018, British author Piu Eatwell also claimed to have identified Short’s killer. In her book Black Dahlia, Red Rose, Eatwell maintains that the culprit wasn’t one murderer but a group of conspirators that included a bellhop and former mortician’s assistant named Leslie Dillon (who had been one of the LAPD’s favorite suspects decades ago), nightclub owner Mark Hansen, and a man named Jeff Connors. Eatwell thinks the police were involved in a cover-up due to their connections with at least one of those men, though she allows that the case will probably never be definitively solved.

SOURCE: MENTAL FLOSS

/WP_001012-56a58ab93df78cf77288ba95.jpg)