Today is the anniversary of the Kent State shooting that killed 4 students and injured 9 more. History.com provides a detailed account of why it happened:

Four Kent State University students were killed and nine were injured on May 4, 1970, when members of the Ohio National Guard opened fire on a crowd gathered to protest the Vietnam War. The tragedy was a watershed moment for a nation divided by the conflict in Southeast Asia. In its immediate aftermath, a student-led strike forced the temporary closure of colleges and universities across the country. Some political observers believe the events of that day in northeast Ohio tilted public opinion against the war and may have contributed to the downfall of President Richard Nixon.

The Vietnam War

American involvement in the civil war in Vietnam—which pitted the communists of the northern part of the country against the more democratic south—had been controversial from its beginnings, and a significant segment of the general public in the United States was against the presence of U.S. armed forces in the region.

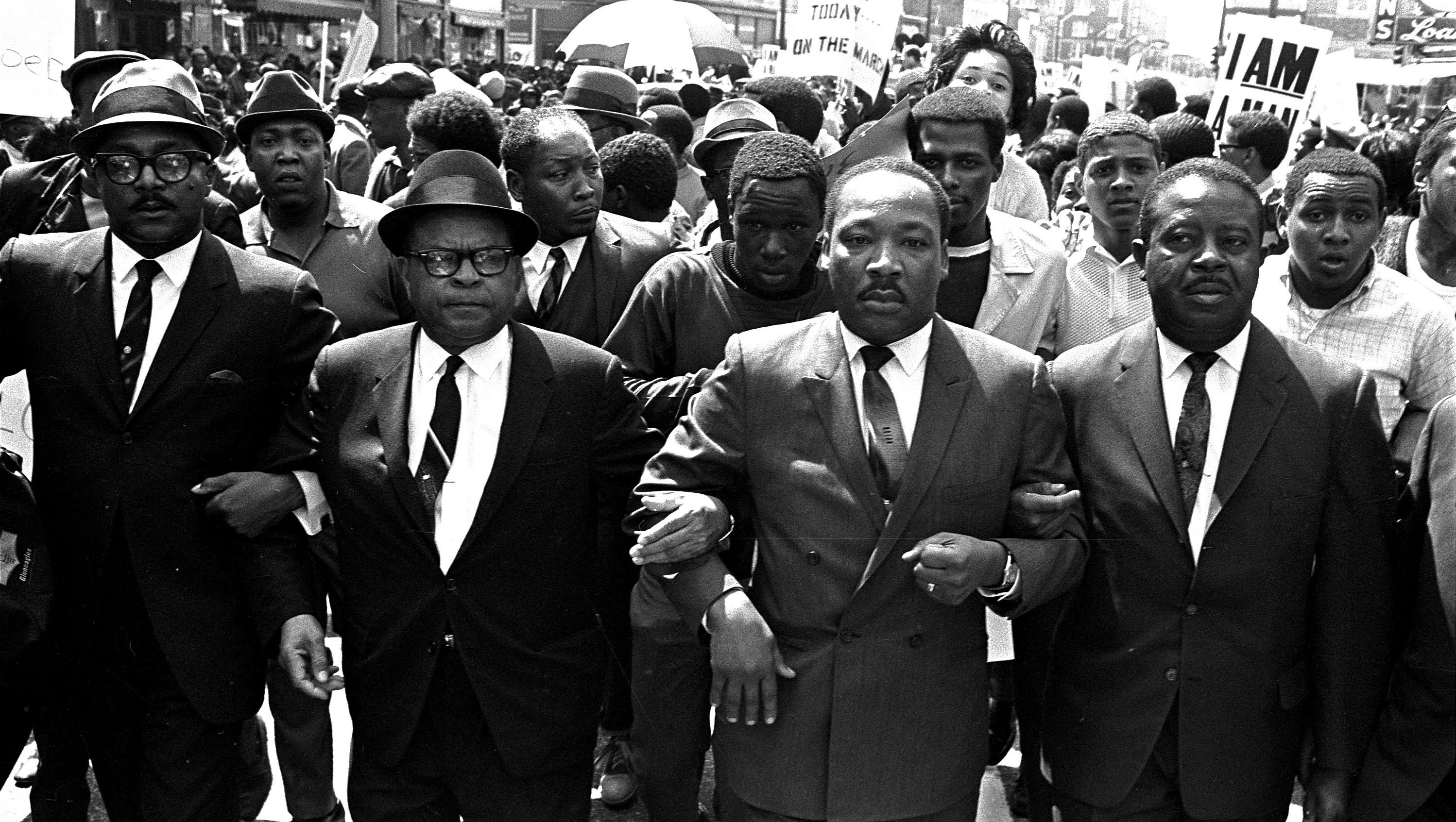

Protests across the country in the latter half of the 1960s were part of organized opposition against U.S. military activities in Southeast Asia, as well as the military draft.

In fact, President Richard M. Nixon had been elected in 1968 due in large part to his promise to end the Vietnam War. And, until April 1970, it appeared he was on the way to fulfilling that campaign promise, as military operations were seemingly winding down.

Invasion of Cambodia

However, on April 30, 1970, President Nixon authorized U.S. troops to invade Cambodia, a neutral nation located west of Vietnam. North Vietnamese troops were using safe havens in Cambodia to launch attacks on the U.S.-backed South Vietnamese, and parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail—a supply route used by the North Vietnamese—passed through Cambodia.

Controversially, the president made his decision without notifying his Secretary of State William Rogers or Defense Secretary Melvin Laird.

They, along with the rest of the American public, found out about the invasion when President Nixon addressed the nation on television two days later. Members of Congress accused the president of illegally widening the scope of U.S. involvement in the war by not receiving their consent through a vote.

However, it was public reaction to the decision that ultimately led to the events at Kent State University, a public university in northeast Ohio.

Vietnam War Protests

Even before Nixon’s formal announcement of the invasion, rumors of the U.S. military incursion into Cambodia resulted in protests at colleges and universities across the country. At Kent State, these protests actually began on May 1, the day after the invasion.

That day, hundreds of students gathered on the Commons, a park-like space at the center of campus that had been the site of large demonstrations and other events in the past. Several speakers spoke out against the war in general, and President Nixon specifically.

That night, in downtown Kent, there were reports of violent clashes between students and local police. Police alleged that their cars were hit with bottles, and that students stopped traffic and lit bonfires in the streets.

Reinforcements were called in from neighboring communities, and Kent Mayor Leroy Satrom declared a state of emergency, before ordering all the bars in the town closed. Satrom also contacted Ohio Governor James Rhodes seeking assistance.

Satrom’s decision to close the bars actually angered the protesters more, and increased the size of the crowds on the streets of town. Police were eventually able to move the protesters back toward campus, using tear gas to disperse the crowd. However, the stage was set for trouble.

Ohio National Guard Arrives

The following day, Saturday, May 2, there were rumors that radicals were making threats against the town of Kent and the university. The threats reportedly were primarily made against businesses in the town and certain buildings on campus.

After speaking with other city officials, Satrom asked Governor Rhodes to send the Ohio National Guard to Kent in an attempt to calm tensions in the area.

At the time, members of the National Guard were already on duty in the region, and thus were mobilized fairly quickly. By the time they arrived at the Kent State campus on the night of May 2nd, however, protesters had already set fire to the school’s ROTC building, and scores were watching and cheering as it burned.

Some protesters also reportedly clashed with firefighters attempting to put out the blaze, and Guardsmen were asked to intervene. Clashes between the Guard and the protesters continued well into the night, and dozens of arrests were made.

Interestingly, the next day, Sunday, May 3, was a fairly calm day on campus. The weather was sunny and warm, and students were lounging on the Commons and even engaging with the Guardsmen on duty.

Still, with nearly 1,000 National Guards at the school, the scene was more like that of a war zone than a college campus.

Protesters and Guardsmen Gather

With a major protest already scheduled for noon on Monday, May 4, once again on the Commons, university officials attempted to diffuse the situation by prohibiting the event. Still, crowds began to gather at about 11:00 that morning, and an estimated 3,000 protesters and spectators were there by the scheduled start time.

Stationed at the now-destroyed ROTC building were roughly 100 Ohio National Guardsmen carrying M-1 military rifles.

Historians have never reached consensus as to who exactly organized and participated in the Kent State protests—or how many of them were students at the university or anti-war activists from elsewhere. But the protest on May 4th, during which activists spoke out against the presence of the National Guard on campus as well as the Vietnam War, was initially peaceful.

Still, Ohio National Guard General Robert Canterbury ordered the protesters to disperse, with the announcement being made by a Kent State police officer riding in a military jeep across the Commons and using a bullhorn to be heard over the crowd. The protesters refused to disperse and began shouting and throwing rocks at the Guardsmen.

Four Dead in Ohio

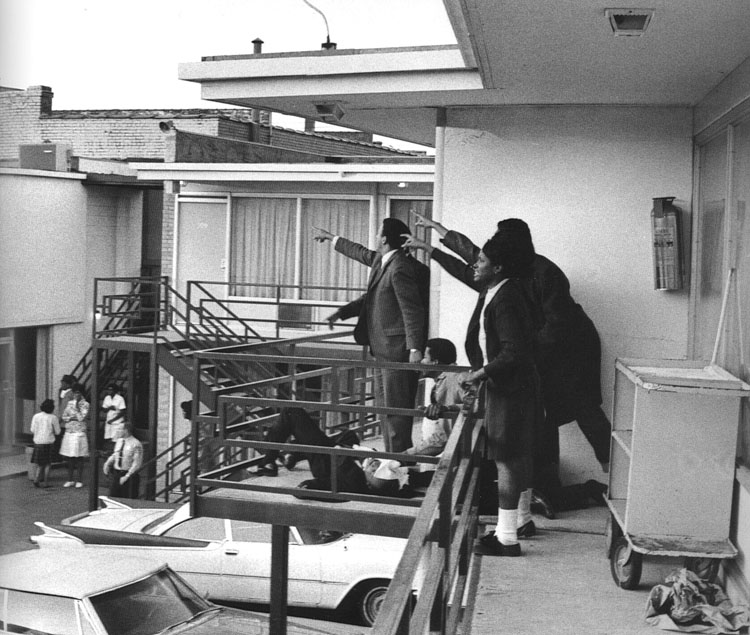

General Canterbury ordered his men to lock and load their weapons, and to fire tear gas into the crowd. The Guardsmen then marched across the Commons, forcing protesters to move up a nearby hill called Blanket Hill, and then down the other side of the hill toward a football practice field.

As the football field was enclosed with fencing, the Guardsmen were caught amongst the angry mob, and were the targets of shouting and thrown rocks yet again.

The Guardsmen soon retreated back up Blanket Hill. When they reached the top of the hill, witnesses say 28 of them suddenly turned and fired their M-1 rifles, some into the air, some directly into the crowd of protesters.

Over just a 13-second period, nearly 70 shots were fired in total. In all, four Kent State students—Jeffrey Miller, Allison Krause, William Schroeder and Sandra Scheuer—were killed, and nine others were injured. Schroeder was shot in the back, as were two of the injured, Robert Stamps and Dean Kahler.

Aftermath of the Kent State Shooting

Following the shooting, the university was immediately ordered closed, and the campus remained shut down for some six weeks following the shootings.

Numerous investigatory commissions and court trials followed, during which members of the Ohio National Guard testified that they felt the need to discharge their weapons because they feared for their lives.

However, disagreements remain as to whether they were, in fact, under sufficient threat to use force.

In a civil suit filed by the injured Kent State students and their families, a settlement was reached in 1979 in which the Ohio National Guard agreed to pay those injured in the events of May 4, 1970 a total of $675,000.

Kent State Shooting Legacy

A signed statement by the Guard, drafted as part of the settlement, read, in part: “In retrospect, the tragedy… should not have occurred. The students may have believed that they were right in continuing their mass protest in response to the Cambodian invasion, even though this protest followed the posting and reading by the university of an order to ban rallies and an order to disperse… Some of the Guardsmen on Blanket Hill, fearful and anxious from prior events, may have believed in their own minds that their lives were in danger. Hindsight suggests that another method would have resolved the confrontation…”

Photographer John Filo won a Pulitzer Prize for his famous image of 14-year-old Mary Vecchio crying over Miller’s fallen body, just after the last shot was fired on the Kent State campus that day. However, this image is hardly the only lasting legacy of the events of May 4.

Indeed, the Kent State shooting remains symbolic of the division in public opinion about war in general, and the Vietnam War specifically. Many believe it permanently changed the protest movement across the American political spectrum, fostering a sense of disillusionment regarding what, exactly, these demonstrations accomplish—as well as fears over the potential for confrontation between protesters and law enforcement.

SOURCE: HISTORY.com

Sources

Personal Remembrances of the Kent State Shootings, 43 Years Later. Slate.

Kent State Shootings. Ohio History Central.

The May 4 Shootings at Kent State University: The Search for Historical Accuracy. Kent State University.

Nixon authorizes invasion of Cambodia, April 28, 1970. Politico.

Was It Legal for the U.S. to Bomb Cambodia? The New York Times.

Photographer John Filo discusses his famous Kent State photograph and the events of May 4, 1970. CNN.

Kent State at 25: A Troubling Legacy. Christian Science Monitor.