Today marks the anniversary of the infamous Boston Massacre. This article from History.com details the events and the aftermath.

From History.com:

The Boston Massacre was a deadly riot that occurred on March 5, 1770, on King Street in Boston. It began as a street brawl between American colonists and a lone British soldier, but quickly escalated to a chaotic, bloody slaughter. The conflict energized anti-British sentiment and paved the way for the American Revolution.

Tensions ran high in Boston in early 1770. More than 2,000 British soldiers occupied the city of 16,000 colonists and tried to enforce Britain’s tax laws, like the Stamp Act and Townshend Acts. American colonists rebelled against the taxes they found repressive, rallying around the cry, “no taxation without representation.” Skirmishes between colonists and soldiers—and between patriot colonists and colonists loyal to Britain (loyalists)—were increasingly common. To protest taxes, patriots often vandalized stores selling British goods and intimidated store merchants and their customers.

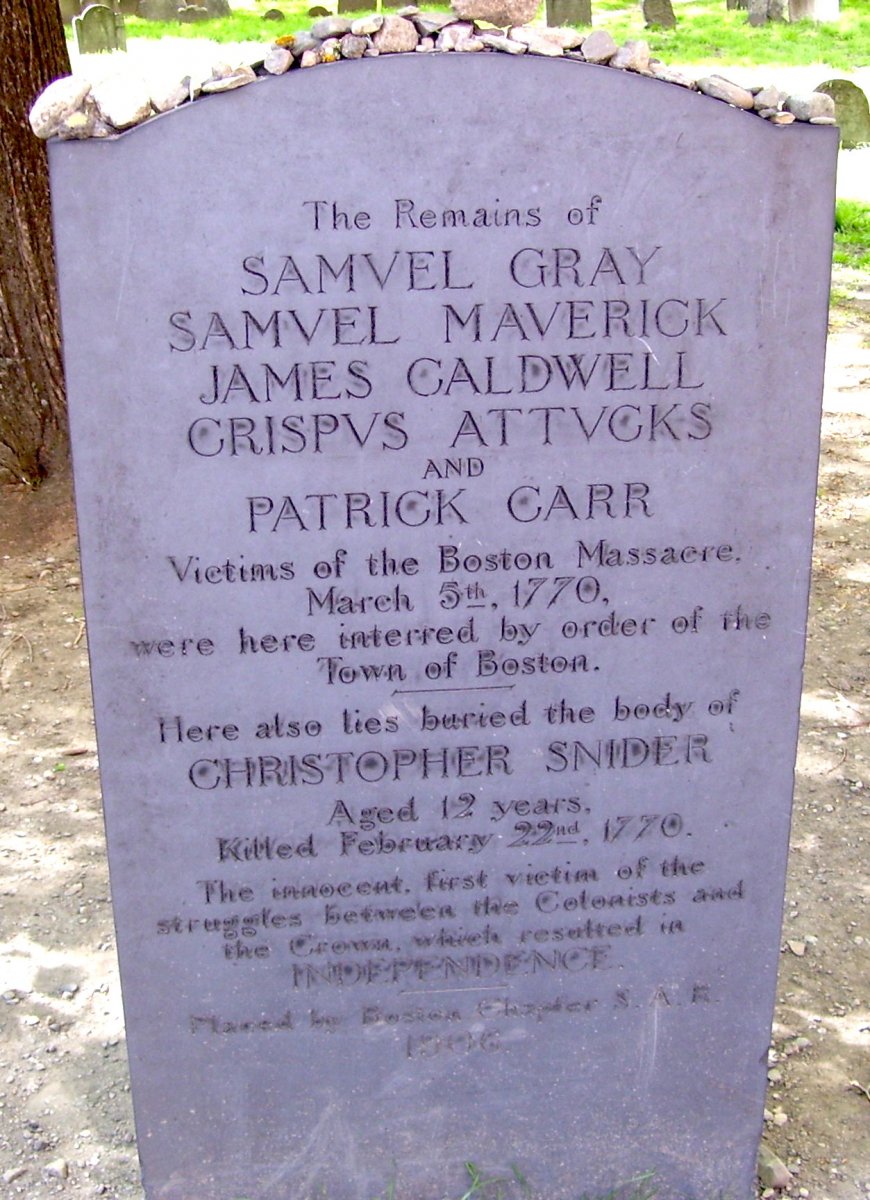

On February 22, a mob of patriots attacked a known loyalist’s store. Customs officer Ebenezer Richardson lived near the store and tried to break up the rock-pelting crowd by firing his gun through the window of his home. His gunfire struck and killed an 11-year-old boy named Christopher Seider and further enraged the patriots. Several days later, a fight broke out between local workers and British soldiers. It ended without serious bloodshed but helped set the stage for the bloody incident yet to come.

On the frigid, snowy evening of March 5, 1770, Private Hugh White was the only soldier guarding the King’s money stored inside the Custom House on King Street. It wasn’t long before angry colonists joined him and insulted him and threatened violence.

At some point, White fought back and struck a colonist with his bayonet. In retaliation, the colonists pelted him with snowballs, ice and stones. Bells started ringing throughout the town—usually a warning of fire—sending a mass of male colonists into the streets. As the assault on White continued, he eventually fell and called for reinforcements.

In response to White’s plea and fearing mass riots and the loss of the King’s money, Captain Thomas Preston arrived on the scene with several soldiers and took up a defensive position in front of the Custom House. Worried that bloodshed was inevitable, some colonists reportedly pleaded with the soldiers to hold their fire as others dared them to shoot. Preston later reported a colonist told him the protestors planned to “carry off [White] from his post and probably murder him.”

The violence escalated, and the colonists struck the soldiers with clubs and sticks. Reports differ of exactly what happened next, but after someone supposedly said the word “fire,” a soldier fired his gun, although it’s unclear if the discharge was intentional. Once the first shot rang out, other soldiers opened fire, killing five colonists–including Crispus Attucks, a local dockworker of mixed racial heritage–and wounding six. Among the other casualties of the Boston Massacre was Samuel Gray, a rope maker who was left with a hole the size of a fist in his head. Sailor James Caldwell was hit twice before dying, and Samuel Maverick and Patrick Carr were mortally wounded. Within hours, Preston and his soldiers were arrested and jailed and the propaganda machine was in full force on both sides of the conflict.

Preston wrote his version of the events from his jail cell for publication, while Sons of Liberty leaders such as John Hancock and Samuel Adams incited colonists to keep fighting the British. As tensions rose, British troops retreated from Boston to Fort William.

Paul Revere encouraged anti-British attitudes by etching a now-famous engraving depicting British soldiers callously murdering American colonists. It showed the British as the instigators though the colonists had started the fight. It also portrayed the soldiers as vicious men and the colonists as gentlemen. It was later determined that Revere had copied his engraving from one made by Boston artist Henry Pelham.

It took seven months to arraign Preston and the other soldiers involved in the Boston Massacre and bring them to trial. Ironically, it was American colonist, lawyer and future President of the United States John Adams who defended them.

Adams was no fan of the British but wanted Preston and his men to receive a fair trial. After all, the death penalty was at stake and the colonists didn’t want the British to have an excuse to even the score. Certain that impartial jurors were nonexistent in Boston, Adams convinced the judge to seat a jury of non-Bostonians.

During Preston’s trial, Adams argued that confusion that night was rampant. Eyewitnesses presented contradictory evidence on whether Preston had ordered his men to fire on the colonists. But after witness Richard Palmes testified that, “…After the Gun went off I heard the word ‘fire!’ The Captain and I stood in front about half between the breech and muzzle of the Guns. I don’t know who gave the word to fire,” Adams argued that reasonable doubt existed; Preston was found not guilty.

The remaining soldiers claimed self-defense and were all found not guilty of murder. Two of them—Hugh Montgomery and Matthew Kilroy—were found guilty of manslaughter and were branded on the thumbs as first offenders per English law. To Adams’ and the jury’s credit, the British soldiers received a fair trial despite the vitriol felt towards them and their country.

The Boston Massacre had a major impact on relations between Britain and the American colonists. It further incensed colonists already weary of British rule and unfair taxation and roused them to fight for independence.

Yet perhaps Preston said it best when he wrote about the conflict and said, “None of them was a hero. The victims were troublemakers who got more than they deserved. The soldiers were professionals…who shouldn’t have panicked. The whole thing shouldn’t have happened.”

Over the next five years, the colonists continued their rebellion and staged the Boston Tea Party, formed the First Continental Congress and defended their militia arsenal at Concord against the redcoats, effectively launching the American Revolution. Today, the city of Boston has a Boston Massacre site marker at the intersection of Congress Street and State Street, a few yards from where the first shots were fired.

SOURCE: HISTORY.COM

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/US0001-Lincoln-Wheat-1926-S-MS65-59c45da96f53ba00105d5460.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8b/26/8b264266-bc6f-43f7-82b3-47af6163e9cc/yokoicave.jpeg)