Yes, that’s NOT a typo. There have been several nominees for Frankensteins in my opinion. But first a warning: some of these segments are quite gruesome, and if you are a dog lover—perhaps watch Young Frankenstein instead and have a few laughs.

Jonathon Dippel

Was “mad scientist” and alchemist Johann Konrad Dippel the inspiration and original model of Mary Shelley’s Victor Frankenstein? Although Mary Shelley never mentioned Dippel or a castle in Germany in any of her previously known writings, the similarities are astonishing.

Johann Konrad Dippel was born in 1673 and died in 1734. He wrote over seventy works and treatises on mathematics, chemistry and philosophy, most written under the pseudonym of Christianus Democritus, with his texts now buried in various academic collections. Dippel was an alchemist, trying to turn base metals to gold, and searching especially for the Philosopher’s Stone and the Elixir Vitae, the secret to extended, if not eternal life.

Dippel was an early chemical manufacturer. He created a concoction called “Dippel’s Oil” or “Dippel’s Animal Oil” used primarily as an agent in the tanning of animal hides, from where it most likely gets its name, and in cloth coloring. It was also said to be useful in calming the pangs and distempers of pregnancy. Whether it was to be used topically, digested, or as an aromatic, is unclear. Its chemical composition with ingredients like Butyronitrile Methylamine and Dimethylpyrrole Valeramide would suggest that ingesting any significant amount would not be very healthy.

Dippel’s connection to Frankenstein comes from his days at the castle on the hilltop near Darmstadt above the Rhine River Valley below Mainz. Johann Dippel was resident there for a time when the castle had fallen vacant of its lordly Franckenstein family owners after the Reformation and the War of European Succession. Dippel tried unsuccessfully to induce the Landgrave of Hesse to deed him the castle in exchange for Dippel’s providing the duke with the secret of everlasting life, the infamous elixir.

He never did come up with a successful Elixir of Eternal Life while at Darmstadt and eventually moved on, with the locals rather chasing him away like those pitchfork wielding villagers in the Universal Frankenstein movies. His permanent acquisition of the castle was opposed and the legends of his making his oil and formulas from the body parts of human corpses was likely an early form of conspiracy theory, born from his boiling animal bones to get ingredients, mixed with the castle’s time as a prison where prisoners were buried in pauper’s graves, and it was hinted that he dug them up to make his concoction, and therefore an easy connection to digging up the dead to bring eternal life.

Dippel moved on from the castle at Darmstadt, still ever seeking his life sustaining elixir, but in the end it may have had the opposite effect. He died of complications of chemical poisoning, either from his close work with some very toxic substances over time, or perhaps sampling his own elixir formula, which may have had the opposite effect than the one intended.

Andre Ure

Andrew Ure was born on May 18, 1778, in Glasgow, United Kingdom. The son of a wealthy cheesemonger, he received an expensive education, studying at both Glasgow University and Edinburgh University. He received his MD from the University of Glasgow in 1801 before spending a brief time with the army, serving as a surgeon. In 1803, he finally settled in Glasgow; becoming a member of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons.

In 1804, at the newly formed Andersonian Institution (now the University of Strathclyde), Ure became a professor of chemistry and natural philosophy. He gave evening lectures on chemistry and mechanics, which he encouraged the average working man and woman to attend. With audiences of up to 500, his lectures inspired the foundation of numerous mechanical institutions throughout Britain.

During this same time, Ure worked as a consultant for the Irish linen board. There he devised his alkalimeter for volumetric estimates of the true alkali contents of various substances that were being used in the linen industry. By this time, he had successfully earned himself a reputation as a highly competent practical chemist.

It was at Glasgow University where Andrew Ure became acquainted with James Jeffray, a professor of anatomy and physiology. Jeffray was a renowned teacher, attracting over 200 students to his classes each year. An innovative surgeon, he is credited (along with Edinburgh obstetrician James Aitken) with the invention of the chainsaw for use in the excision of diseased bone. As a teacher in anatomy, a field that was growing in demand, his options for teaching instruments were limited. The only legal supply of material for dissection was the bodies of hanged criminals. On November 4, 1818, Ure joined Jeffray in the dissection of one such criminal.

Matthew Clydesdale was a weaver, arrested and found guilty of murdering a 70 year old man in a drunken rage. He was sentenced to death by hanging, and on November 4, 1818, that execution was carried out. Upon his death, his body was placed in a cart and transported up to Glasgow University and into the Anatomy Theatre.

During this time, people, especially scientists, were fascinated with electricity. In fact, in 1780, Italian anatomy professor, Luigi Galvani, discovered that by utilizing sparks of electricity he could make a dead frog twitch and jerk. This discovery quickly led to others experimenting with electrical currents on other animals. Shows were made where scientists would electrify the heads of pigs and bulls.

James Jeffray and Andrew Ure would take that experiment one step further. The crowd gathered in the Glasgow University Anatomy Theatre where they would learn what would happen when electricity was exposed to a deceased human body.

With his galvanic battery charged, the experiments commenced.

Incisions were made at the neck, hip, and heels, exposing different nerves. Ure stood over the body, holding two metallic rods, charged by a 270 plate voltaic battery. Those rods, when placed to the different nerves, caused the body to convulse and writhe. When the rods were touched to Clydesdale’s diaphragm, his chest heaved then fell. “When the one rod was applied to the slight incision in the tip of the forefinger,” Ure later described to the Glasgow Literary Society, “the fist being previously clenched, that finger extended instantly; and from the convulsive agitation of the arm, he seemed to point to the different spectators, some of whom thought he had come to life.”

The experiment lasted about an hour. Ure wrote his account of the experiment, and even delivered a lecture. Ure and Jeffray did not bring Matthew Clydesdale back to life, though they did not believe it was a failure on their methodology. Instead, Ure believed that if his death had not been caused by bodily injury, there was a possibility that his life could have been restored. He also noted that if their experiment had succeeded in bringing him back to life, it would not have been celebrated. After all, he was a murderer.

The story eventually took on a life of its own. Memories and accounts differed, and one such account is that of Peter Mackenzie. In 1865, Mackenzie claimed to have been present at the Glasgow University Anatomy Theatre that day. He claims that Ure had actually been successful, and Clydesdale had been brought back to life. To abate the risen fear among the crowd, one of the scientists grabbed a scalpel and slit his throat. Clydesdale fell down, once again, dead.

Robert Cornish

Tales of Mad Scientists have been in existence for centuries now. And while many are criticized for being wacky, inhumane and downright psychopathic many can also be celebrated for making breakthroughs within various scientific fields–especially within the field of medicine where procedures today have origins from millennia ago; in medieval times and before them in prehistory. One such tale with a more modern spin comes from the 1930s in Berkley, California where an American called Robert Cornish attempted to bring the dead back to life.

Cornish was a medical phenomenon, graduating at 18 from the University of California and gaining a Doctorate at 22. He was a handsome chap but his eccentricity was soon apparent as one of his invention concepts was a pair of spectacles to allow the reading of newspapers underwater. This may illustrate his intelligence; however as to gain a patent in those times was considered very noteworthy and could propel a person to fame. Cornish worked at the Department of Experimental Biology at a University when he began to get notoriety for something of a darker nature than underwater specs.

Dog-lovers read no further. Cornish began an experiment to cure the undead but not permitted to use human beings he had to operate on dogs. The doctor organized a public demonstration which Time magazine witnessed. He named his patients – five fox terriers – Lazarus after the mythical figure brought back to life by Jesus.

Robert Cornish tried many different techniques before gaining moderate success with the following. He would suffocate the animals first with either Nitrogen or ether. He would wait no more than five minutes after the heart had stopped to try and resuscitate. To do this he found a way to keep the blood circulating by using a piece of wood called a teeterboard, a type of see-saw to rock the patient up and down to maintain the circulation of blood.

Before re-animation, he would inject the creature with a concoction of saline, oxygen, adrenaline, blood as well as anti-coagulants and coagulants. Oxygen would be blown into the mouth via a rubber tube. Bear in mind this was in the 1950s when CPR and techniques of the sort were in their infancy meaning his methods were extremely right-field.

The first three dogs were revived but showed little signs of life after. The best result was Lazarus II who was in a coma for eight hours before passing again. The fourth dog – Lazarus IV – came back to life albeit blind and brain-damaged, Cornish reported that she recovered to near full strength in a matter of months. Lazarus V was the same but returned to normality in shorter time. These are the words of Doctor Cornish only however and were not confirmed by Time or anyone else it appears. Despite these factors, Cornish hailed his experiments a success.

The mad-cap doctor was heavily criticized and eventually fired from the UCLA Laboratory when protestations about the canine killings reached their ears. He was forced to do his experiments in the confines of his own abode and with pigs rather than dogs.

Requiring funding, Robert Cornish tried to clear his name by convincing people that his work was vital. This was through a movie titled ‘Life Returns’. Cornish played himself as does one of the Lazarus dogs. It uses a familiar aspect to pull at the heartstrings of the audience, with the doctor attempting to resurrect his son’s dead dog. It was the only way his son would love him again after all. The film was far from a success and ergo did nothing to improve the reputation of the doctor.

His next plan was to find a human patient. He searched the jails and found a willing convict called Thomas McMonigle, an inmate of San Quentin prison, convicted of killing a fourteen-year-old girl. The government declined the request on compassionate grounds. There is another rumor however which seems to be justified by newspaper reports from the time. This relates to the courts fearing a ‘double jeopardy’ clause. Death by the gas chamber which would have released the convict from his conviction and therefore he would have been a free man.

Vladimir Demikhov

Calling Soviet doctor Vladimir Demikhov a mad scientist may be undercutting his contributions to the world of medicine, but some of his radical experiments certainly fit the title. Case in point — though it may seem like myth, propaganda, or a case of photoshopped history — in the 1950s, Vladimir Demikhov actually created a two-headed dog.

Even before creating his two-headed dog, Demikhov was a pioneer in transplantology — he even coined the term. After transplanting a number of vital organs between dogs (his favorite experimental subjects) he aimed, amid much controversy, to see if he could take things further: He wanted to graft the head of one dog onto the body of another, fully intact dog.

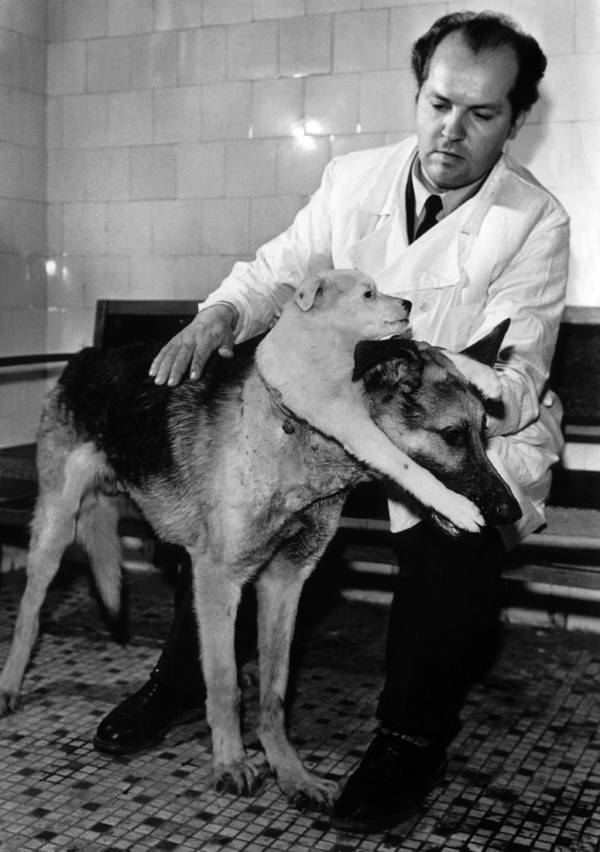

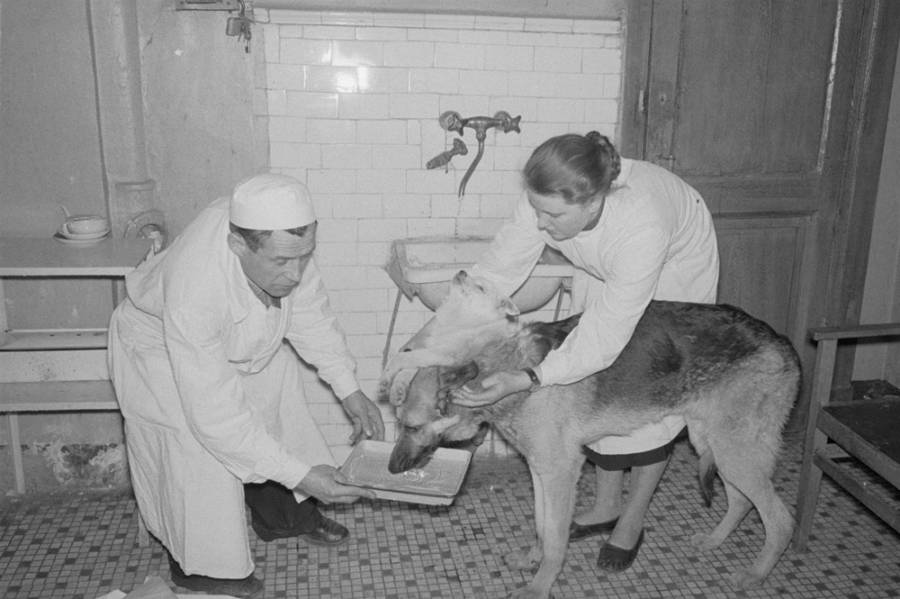

He was “successful”. In the above picture, laboratory assistant Maria Tretekova lends a hand as noted Russian surgeon Dr. Vladimir Demikhov feeds the two-headed dog he created by grafting the head and two front legs of a puppy onto the back of the neck of a full-grown German shepherd.

{{SHUDDER}}

I can’t leave the reader with such horrible images…let’s end with some happy, funny ones instead.

LikeLiked by 1 person

awwwww

LikeLiked by 1 person

and thanks for all the morning videos!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoy

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 1 person

wow…she’s delusional too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

hey that’s so awesomely cool!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

😁

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 1 person

he’s gone

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

if President Trump said that…it would be CATASTROPHIC!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

and we need 87,000 MORE of them?

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

the buckets were at least useful!

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

the buck was nice till the end…LOL

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

LikeLiked by 1 person

she’s not living in Chicago…she’s living in DENIAL

LikeLiked by 1 person

🤣👍

LikeLike

LikeLiked by 1 person