TAKES THE CAKE: The phrase “takes the cake” comes from the cake walks that were popular in the late 19th century. Couples would strut around gracefully and well-attired, and the couple with the best walk would win a cake as a prize. Interestingly, cake walk was soon used to describe something that could be done very easily, and it’s very possible that from there we get the phrase “piece of cake.”

PARTING SHOT: A parting shot, which is a final insult tossed out at the end of a fight when you assume it’s over, was originally a Parthian shot. The Parthians, who lived in an ancient kingdom called Parthia, had a strategy whereby they would pretend to retreat, then their archers would fire shots from horseback. Parthian sounds enough like parting, and, coupled with the fact that not a lot of people knew who the Parthians were, the phrase was changed to parting shot.

DEAD AS A DOORNAIL: One could certainly argue that a doornail was never alive, but when a doornail is dead, it has actually been hammered through a door, with the protruding end hammered and flattened into the door so that it can never come loose or be removed or used again. The phrase “dead as a doornail” has actually been around since the 14th century, about as long as the word doornail has officially been in the English language.

DOWN TO BRASS TACKS: “There are many theories about what “down to brass tacks” means, including that brass tacks is rhyming slang for hard facts. But it’s very likely that the brass tacks being mentioned here are actual brass tacks. Merchants used to keep tacks nailed into their counters to use as guides for measuring things, so to get down to brass tacks would be you were finally done deciding what you wanted and were ready to cut some fabric and do some actual business.

IT’S GREEK TO ME: “The phrase “it’s Greek to me” is often attributed to Shakespeare, but it’s been around since well before his time. An earlier version of the phrase can be found written in Medieval Latin translations, saying “Graecum est; non potest legi,” or “it’s Greek. Cannot be read.”

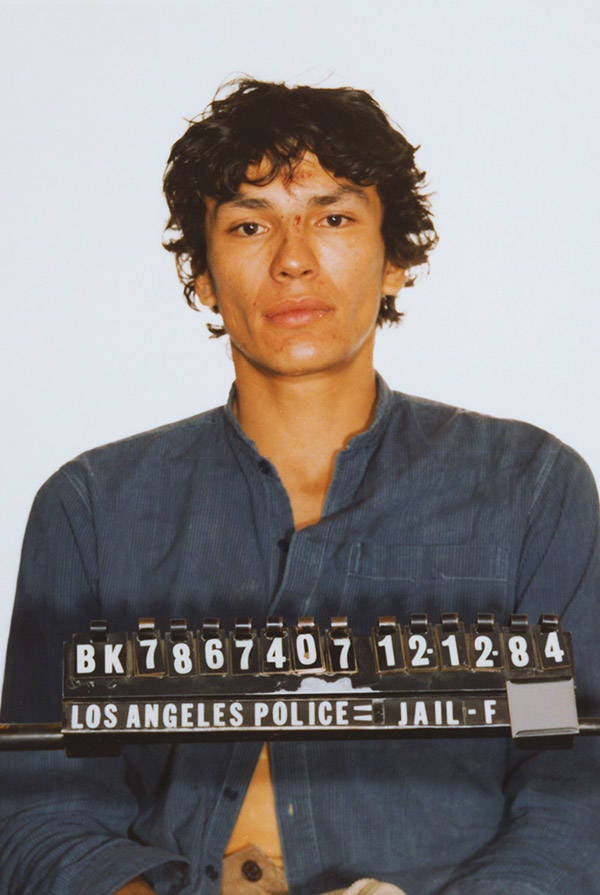

SMART ALEC: “You may have presumed the Alec in “smart Alec” was just a name that sounded good preceded by the word smart, but that’s not necessarily the case. Professor Gerald Cohen suggested in his book”Studies in Slang” that the original smart Alec was Alexander Hoag, a professional thief who lived and robbed in New York City in the 1840s. Hoag was a very clever criminal who worked with his wife and two other policemen to pickpocket and rob people. He was eventually busted when he decided to stop paying the cops.

HEARD IT THRU THE GRAPEVINE: “The grapevine people hear things through is a grapevine telegraph, which was the nickname given to the means of spreading information during the Civil War as a kind of wink at an actual telegraph. The grapevine telegraph is just a person-to-person exchange of information, and much like when you play a game of telephone, it’s best to presume that the information you receive has gone through a few permutations since it was first shared.

CAT’S OUT OF THE BAG: “Farmers used to stick little suckling pigs in bags to take them to market. But if a farmer was trying to rip somebody off, they would put a cat in the bag instead. So, if the cat got out of the bag, everybody was onto their ruse, which is how we use the phrase today, just not quite so literally. (We hope.)

OUT OF WACK: “Today, “out of whack” means not quite right, but it took a long time to get there. Whack appeared in the 18th century as a word that meant to strike a blow when used as a verb. The noun whack was the blow that was whacked on something. But whack also grew to mean portion or share, especially as loot that was being split by criminals. From there, whack grew to mean an agreement, as in the agreed share of loot, but it also meant in good order. If something was behaving as it was intended to, it was “in fine whack.” Eventually the opposite fell into common usage, and something that wasn’t in good shape was “out of whack.”

KIBOSH: “Evidence of kibosh dates the word to only a few years before Charles Dickens used it in an 1836 sketch, but despite kibosh being relatively young in English its source is elusive. Another hypothesis pointed to Irish caidhp bhais, literally, coif (or cap) of death, explained as headgear a judge put on when pronouncing a death sentence, or as a covering pulled over the face of a corpse when a coffin was closed. Today, “to put the kibosh on something” is to shut it down.

BETWEEN A ROCK AND A HARD PLACE: “Some people think that the phrase “between a rock and a hard place” is a kind of sloppy reference to Odysseus. But in 1921, the phrase became a popular means of describing when miners had to choose between dangerous work for little or no money or definite poverty during the Great Bankers’ Panic of 1907.

GOT UP ON THE WRONG SIDE OF THE BED: “The generally accepted origin of the phrases “get up on the wrong side of the bed” and wake up on the wrong side of the bed is ancient Rome, where superstition was rampant. Ancient philosophers equated the right side of anything as the positive side, and the left side of anything as the sinister or negative side. The story says that Romans always exited the bed on the right side in order to start the day in contact with positive forces. If one rose on the left side of the bed, he started the day in contact with negative forces.

MAD AS A HATTER: “The expression is linked to the hat-making industry and mercury poisoning. In the 18th and 19th centuries, industrial workers used a toxic substance, mercury nitrate, as part of the process of turning the fur of small animals, such as rabbits, into felt for hats. Workplace safety standards often were lax and prolonged exposure to mercury caused employees to develop a variety of physical and mental ailments, including tremors (dubbed “hatter’s shakes”), speech problems, emotional instability and hallucinations.