From All That’s Interesting:

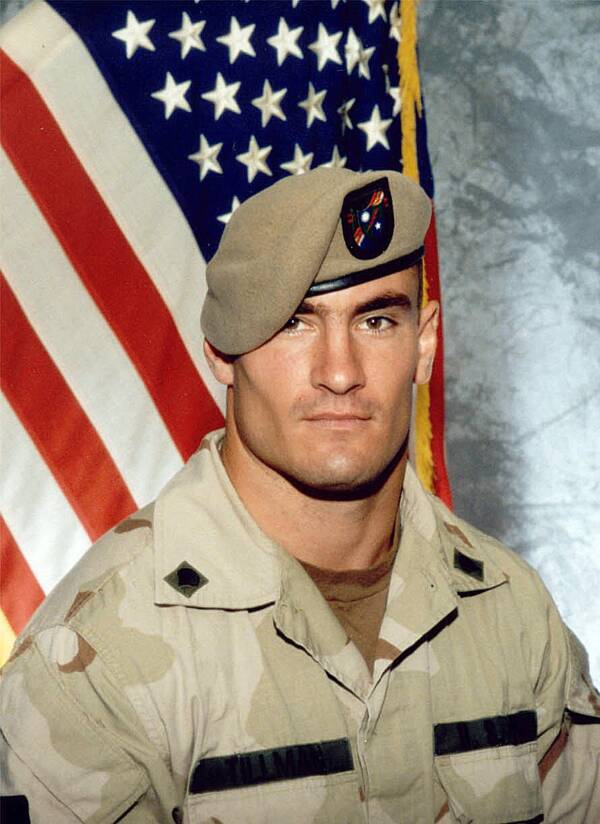

On April 22, 2004, former NFL star and U.S. Army Ranger Pat Tillman was killed by friendly fire in Afghanistan — and it may not have been an accident. After the 9/11 attacks, Pat Tillman gave up a lucrative football career to join the U.S. Army. But in 2004, he was tragically killed by the Taliban — or so his family and the American public were led to believe.

As the story went, Tillman had bravely rescued dozens of his fellow soldiers before he was gunned down by enemy forces in Afghanistan. Unsurprisingly, the American media quickly hailed Tillman as a war hero. Helicopters flew over football stadiums in his honor. A televised memorial service was planned. Top-ranking officers called for Tillman to be posthumously awarded the Silver Star and the Purple Heart

But as Tillman’s family mourned their loss, they had a feeling that something wasn’t quite right. And though his mother pressed the Army for more details, they stuck to their initial story about Pat Tillman’s death.

Around this same time, anti-war voices were getting louder in the United States. And photos of the torture at the Abu Ghraib prison were about to become public. Thus, Tillman seemed like the perfect poster boy for America’s “War on Terror.” But this couldn’t have been further from the truth. Several weeks later, the real story finally came out: Tillman had been killed by friendly fire, not the Taliban. As if that weren’t bad enough, the circumstances surrounding his death were highly suspicious.

The Story Of A Football Star Turned Soldier

Patrick Daniel Tillman was born on November 6, 1976, in San Jose, California. The oldest of three brothers, he was a natural athlete and led his high school football team to the Central Coast Division I Football Championship. As a result, he soon earned a scholarship to Arizona State University. While in college, Tillman led his team to an undefeated season and was named Most Valuable Player of the Year in 1997. After the Arizona Cardinals drafted him into the NFL in 1998, Tillman became a beloved starting player and broke the team record for the most tackles two years later.

However, everything changed for Tillman after he watched the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States play out on live television. “My great grandfather was at Pearl Harbor,” he told NBC News on September 12, 2001, “and a lot of my family has… fought in wars, and I really haven’t done a damn thing as far as laying myself on the line like that.”

Tillman famously turned down a $3.6 million, three-year contract with the Cardinals, choosing instead to enlist in the U.S. Army in May 2002.

Pat Tillman and his brother Kevin trained to become Army Rangers — elite soldiers who specialize in joint special operations raids. They were eventually assigned to the 2nd Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment, based in Fort Lewis, Washington. And in 2003, they were deployed to Iraq. But significantly, Pat Tillman was against the Iraq War. He was prepared to go to Afghanistan — where the war effort had begun — but he was not happy to hear that the focus was now on a different country.

Tillman had intended to fight against Al Qaeda and bring Osama bin Laden to justice. But the Bush administration had pivoted to Iraq to track down Saddam Hussein and his alleged weapons of mass destruction. That wasn’t what Tillman had signed up for, but he went anyway. Just one year later, Tillman’s second tour would take him to Afghanistan — where he would tragically die at age 27.

The Story Of Pat Tillman’s Death

As his service began, Tillman noticed differences between his experience in the war and its depiction in the media. For instance, he was assigned to a unit that would help release a POW named Jessica Lynch from Iraqi forces in 2003, and he saw firsthand the media’s sensationalized spin on the story. While the military portrayed Lynch as being in extreme danger, she had actually been taken care of by Iraqi doctors in a hospital. Lynch herself would later blast the national press for nurturing a skewed narrative before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform in 2007.

“I’m still confused as to why they chose to lie and try to make me a legend when the real heroics of my fellow soldiers that day were legendary,” she said, insisting that the sensationalization was unnecessary. “The truth of war is not always easy to hear but [it’s] always more heroic than the hype.” At the time the rescue was happening, Tillman described the military’s elaborate tale as “a big public relations stunt.” But after his death on April 22, 2004, he would become the subject of one himself.

Initial reports stated that Tillman was killed by enemy fire during an ambush in the Khost Province of southeastern Afghanistan. His family and the American public alike were told that Tillman had bravely hustled up a hill to force the enemy to withdraw — saving dozens of his comrades in the process. Tillman was quickly declared a hero.

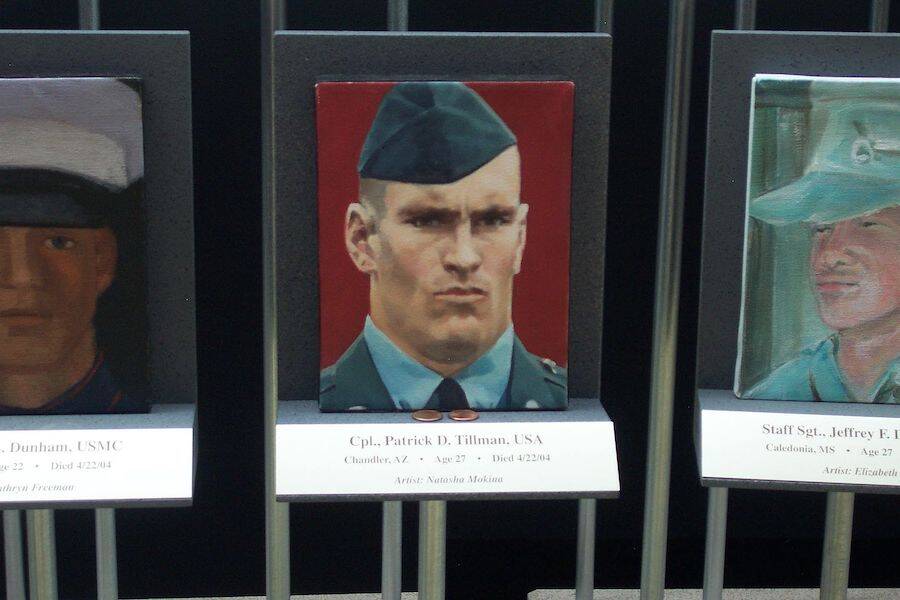

Shortly after the 27-year-old’s death, top-ranking officers were saying that he should receive the Silver Star and the Purple Heart. And he was soon honored at a nationally televised memorial service on May 3, 2004. There, Senator John McCain, a veteran himself, delivered Tillman’s eulogy. But despite the widespread praise and glory, Pat Tillman’s family couldn’t shake the feeling that they weren’t being told the real story about his death. And they were sadly correct.

How Did Pat Tillman Die?

About a month after Pat Tillman’s death, the Army came forward with a shocking announcement. Tillman had not been killed by insurgents — he was shot down by his fellow soldiers. As they took aim at him, he yelled, “I’m Pat f**king Tillman!” to get them to stop. It was the last thing he ever said. Tillman’s mother Mary was later asked how long she thought it took for the Army to realize what had really happened. And she responded, “Oh, they knew immediately. It was pretty evident right away. All the other soldiers on the ridgeline suspected that that’s exactly what happened.”

While the shooting has since been described as accidental, some have their doubts. Not only was Tillman shot three times in the head, but he was also shot at close range and there was no evidence of any enemy fire in the area — unlike the Army’s initial report of the incident. So if there were no enemies nearby, what were the American soldiers shooting at?

In 2007, it was revealed that Army doctors who examined Tillman’s body were “suspicious” of the close proximity of the bullet wounds on his head. They even tried — and ultimately failed — to convince authorities to investigate the death as a potential crime because “the medical evidence did not match up with the scenario as described.”

The doctors believed that Tillman had been shot by an American M-16 rifle from just 10 yards away. But despite the worrying details in this report, it was apparently shelved and not released to the public for years. Eerily, it was also discovered that Tillman’s personal items had been burned — including his uniform and private journals. And those who were present during his death were told to keep quiet about what actually happened.

As it turned out, Pat Tillman’s brother Kevin was on the same mission that day. But Kevin was not present when Pat was killed. So naturally, the secret had to be kept from him as well. Much like his mother, Kevin was initially left in the dark about how Pat Tillman died. And even when the truth came out about the friendly fire, they still felt like they weren’t getting all the details.

Desperate for answers, Tillman’s mother had to spend years fighting through multiple investigations and Congressional hearings to piece the whole story together. And she was horrified by the amount of Army misinformation that had clouded the truth about her son’s demise.

“They had no regard for him as a person,” Mary Tillman said. “He’d hate to be used for a lie.”

Indeed, Jon Krakauer’s Tillman biography Where Men Win Glory revealed that Tillman told a friend after enlisting: “I don’t want them to parade me through the streets [if I die].” Tragically, the government had done just that. And the fact that it was based on a false story made the situation even worse. While there were some soldiers who wanted to tell the truth, they were allegedly silenced. In April 2007, Specialist Bryan O’Neal — the last person to see Tillman alive — testified that his superiors had warned him not to tell the media nor the Tillman family about the friendly fire.

And in July of that same year, two prominent lawmakers of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform accused Bush officials and the Pentagon of actively withholding documents on the death. The actions of the military and government have led to the disturbing theory that Tillman was murdered for his views on the Iraq War.

The Legacy Of Pat Tillman

On the surface, Pat Tillman appeared to be the poster boy for America’s multiple wars in the Middle East. A clean-cut all-American, Tillman had gone from being a sports hero to a war hero. But the reality was more complicated. As an anti-war atheist who quickly became disillusioned with the War on Terror, Tillman was quite heterodox for someone in the military. And he wasn’t shy about sharing his views with fellow soldiers while he was deployed in Afghanistan.

While many American soldiers insisted that Tillman was a well-respected Ranger and had no major enemies in the Army, it’s not unreasonable to think that some officers may have had a problem with some of Tillman’s views — especially since he didn’t hesitate to speak his mind. During the lead-up to the 2004 election, Tillman was rumored to be planning to go public with his opposition to the invasion of Iraq and President Bush. He may have even planned to express these views in a televised meeting with Noam Chomsky. But this meeting never happened.

Because of all of this, some insist that Pat Tillman’s death was no accident. The cynicism behind this theory only worsened in 2007, when it was proven that “Army attorneys sent each other congratulatory e-mails for keeping criminal investigators at bay as the Army conducted an internal friendly-fire investigation that resulted in administrative, or non-criminal, punishments.”

While the particulars of the friendly-fire incident remain vague to this day, a few things are clear. Pat Tillman enlisted to fight against those who had planned the 9/11 attacks. Instead, he was deployed to Iraq during an invasion and occupation that he reportedly called “f**king illegal.” Tillman was clearly disillusioned with the war and started to speak out about this — just before he was shot by his own men. But instead of being honest about Pat Tillman’s death and the events leading up to it, the Army transformed him into an unwitting advocate for the War on Terror.

That said, his family fought for the truth about what happened to their loved one — and they were able to expose many layers of deception along the way. Only time will tell if more revelations emerge in the years to come. But if they do, his family will surely be ready to tell the world. “This isn’t about Pat, this is about what they did to Pat and what they did to a nation,” said Tillman’s mother. “By making up these false stories you’re diminishing their true heroism. It may not be pretty but that’s not what war is all about. It’s ugly, it’s bloody, it’s painful. And to write these glorious tales is really a disservice to the nation.”

SOURCE: ALLTHATSINTERESTING.COM

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/d9/0e/d90e4c27-750c-4326-b268-e6513f447b4e/22-lind-new-ii.jpg)