FROM: COWBOYSTATEDAILY:

R.J. “Gill” Gillilan would often sit in the corner of the room, sporting a leather coat and gold chains or, at other times, bib overalls when he didn’t want to be bothered by anyone. He was in Las Vegas, Nevada as an undercover “john” on what his wife, Carmalen, called “smut patrol.”

Gillilan had planned his personal vacations meticulously and always looked forward to leaving behind the glitz of Sin City for the sage and dirt of Wyoming. He had been drawn back to his boyhood home by a portrait of a horse.

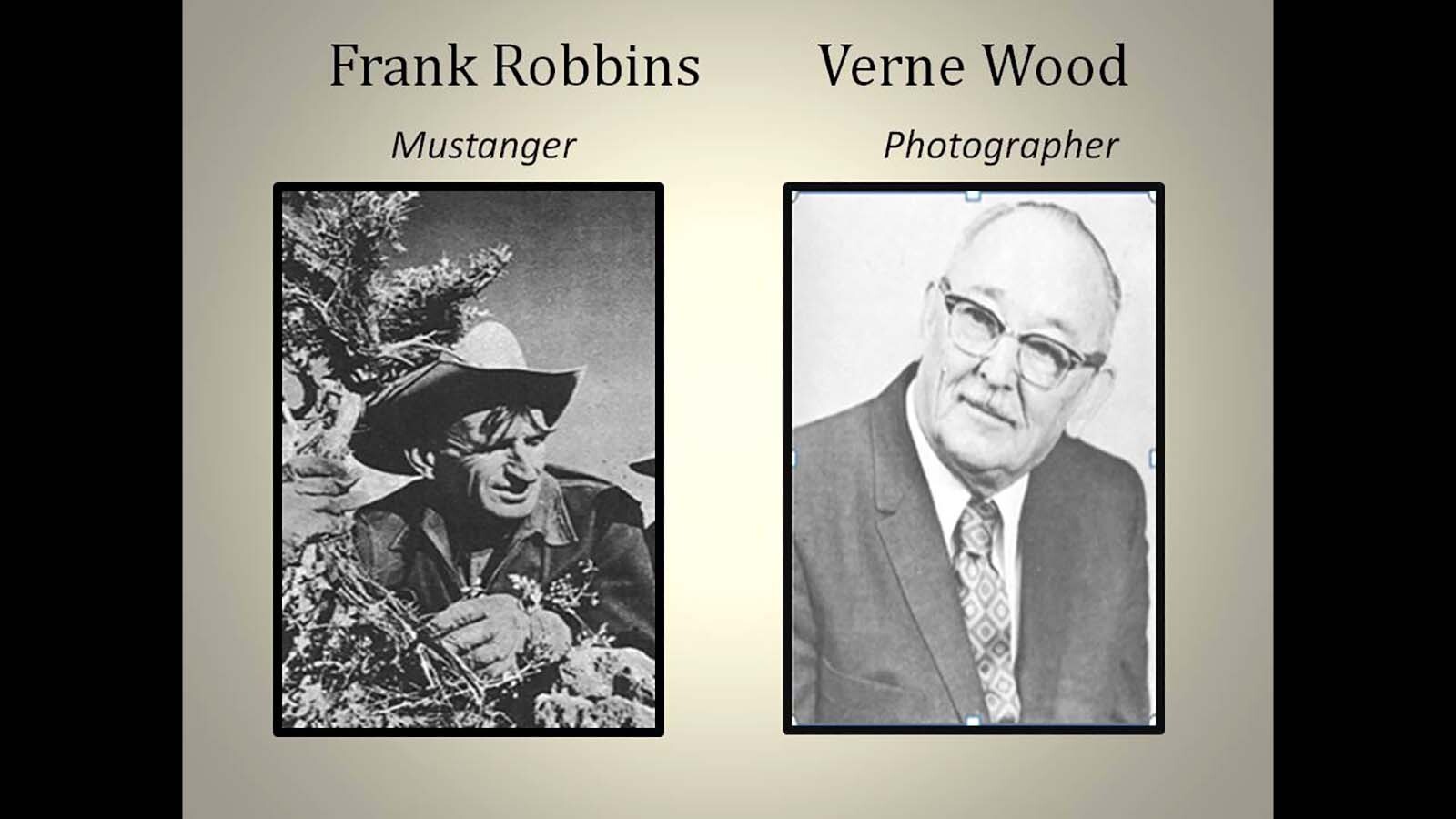

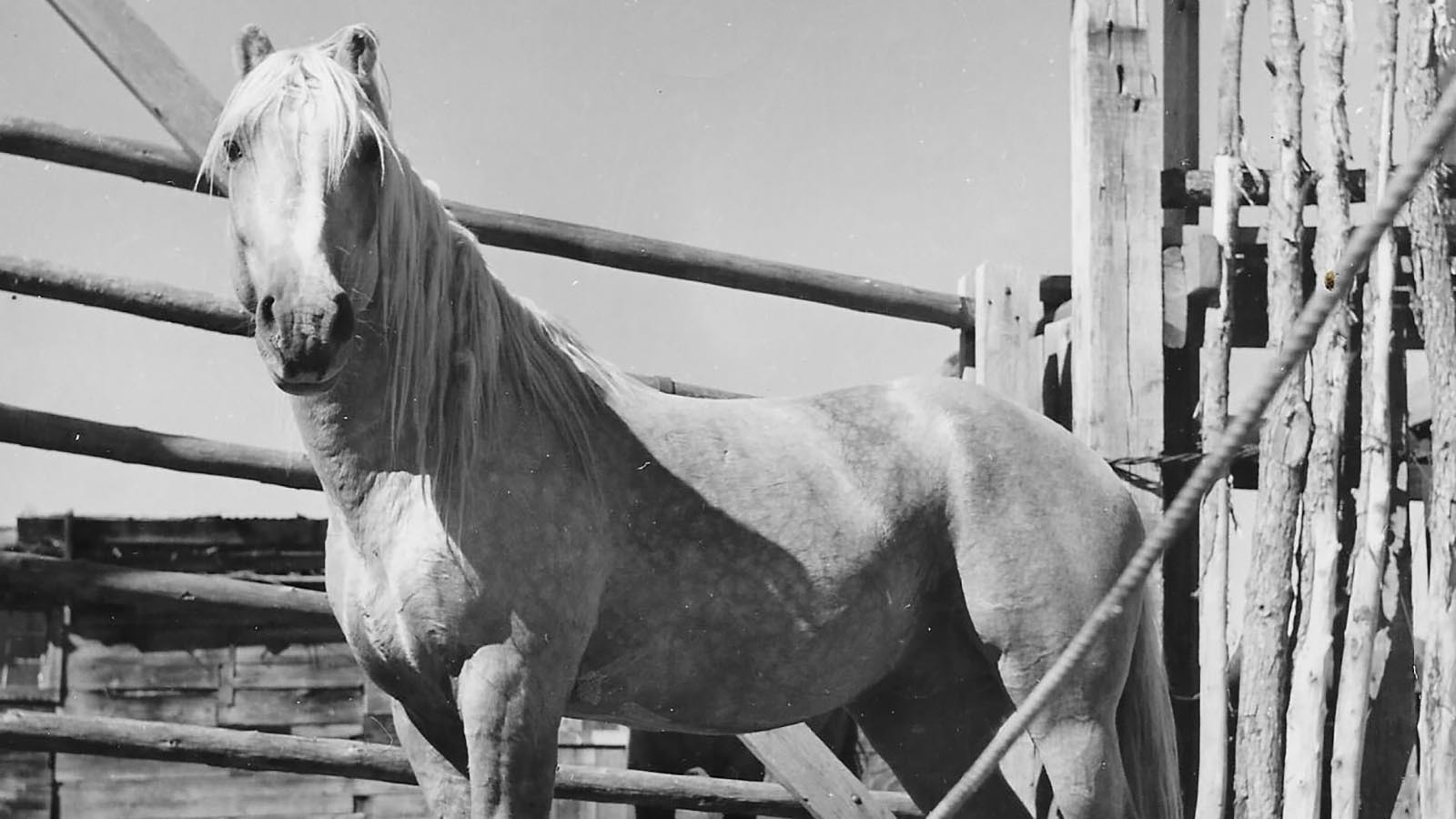

Eighty years ago, Frank “Wild Horse” Robbins was rounding up mustangs with an airplane in the Red Desert near Rawlins, Wyoming, when he spotted a rare palomino stallion running with the herd. He sent for his photographer, Verne Wood, to take a photo, unaware of the sequence of events that he was about to unleash.

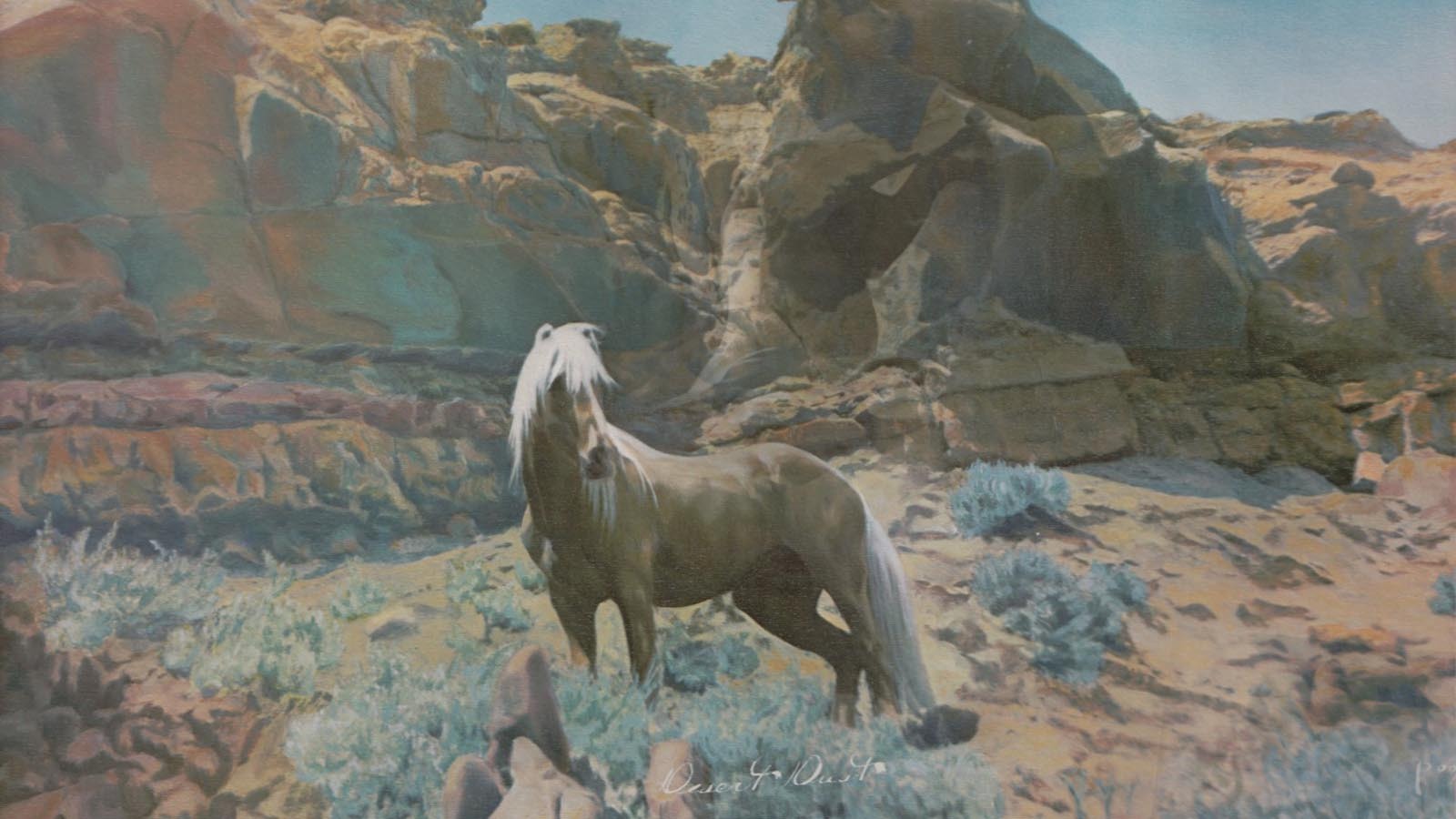

This photo caught the imagination of the world. The horse, now known as Desert Dust, had posed in sage and rock the day of his capture, still untamed and wild. More than a million copies were sold worldwide appearing at such prestigious places as the House of Commons in London.

Wood hired a team to colorize the copies he sold, and life was good. However, his good fortune was about to change. Realizing the stunning popularity of his horse, Robbins sued for the rights of the famous photo, especially since now he planned to shoot a movie about Desert Dust with Universal Studios. It was this first photo of Desert Dust that sparked an investigation by the Las Vegas detective into just who this horse was. What began as mere curiosity of a wild horse ballooned into a lifelong passion to tell the true tragic story of Desert Dust.

The Spark of an Investigation

Desert Dust was once the most famous Wyoming horse in the world, but by the time Gillilan was in high school in the 1960s, the memory of the wild stallion was beginning to fade and only tall tales seemed to remain. Desert Dust’s photo hung in nearly every important building in Rawlins, including Gillilan’s high school, and everyone knew his name but not much else.

“I was always interested in the story of Desert Dust,” Gillilan said. “My granddad was really mad about the dog food thing.” Many of the wild horses in the early days were slaughtered after their capture for dog food. His grandfather hated to see these symbols of America destroyed like that and it colored Gillilan’s own story of all the horses, including Desert Dust.

Gillilan’s earliest memories of Desert Dust’s owner, Frank Robbins, was his grandpa glaring at the horse wrangler in unconcealed contempt at a wild horse sale. Robbins had used airplanes to catch Desert Dust and the horse had died in his care. It also didn’t help that his grandpa’s neighbor and friend was a horse wrangler in competition with Frank Robbins.

“Typical small town,” Carmalen, Gillilan’s wife, said. “You have to take one side or the other. You can’t both be true.” These memories of his childhood prompted Gillilan to eventually buy his own tinted portrait of Desert Dust and hang it in his house. It became more than a photo and a story began to emerge after his daughter, Kyla, asked an innocent question.

She wanted to know who the horse was and Gillilan had given her the basic answer he knew. Desert Dust had been the first wild stallion ever captured by an airplane and this horse was the inspiration of his Rawlins high school mascot, the Outlaws. However, he was about to prove himself wrong. The longer he pondered the question of just who Desert Dust really was, the more doubt crept in and the investigator in him took over. Gillilan may not have had any formal training as a historian, but he knew how to find the clues that would tell the story.

For the next 20 years, his vacations involved chasing down the facts about Desert Dust and knocking on the doors of strangers. He dragged his family into remote canyons, learned how to surf the web and went wherever the trail led him. This hard-boiled detective was determined to learn the truth about Desert Dust, no matter how long it took. Slowly, the story began to emerge.

The Famous Photo

On the morning of July 12, 1945, after getting the call from horse wrangler Robbins, Wood had snapped a black-and-white photo of Desert Dust. Even as he took the photo, his family said he knew that he had just captured the photo of a lifetime. “It was about a week before the atomic bomb was tested in New Mexico,” Gillilan said, noting the timeline. “The war wasn’t over yet when they developed this picture.”

Wood was the first one to announce the name of the wild palomino and started selling black and white copies to others besides Robbins. As the picture’s popularity started to grow, Wood started colorizing his photos and then he hit it big. “Verne really started selling a lot of them after he submitted the picture to the Denver Post and won the contest,” Carmalen said.

In the late 1940s, everybody that was in agriculture that could went to Denver for the stock show and the national western show. The newspaper contest announced their winner when this crowd was in town and people from all over the country saw the picture as a result. Sales rocketed. “He started hiring gals to come in and do the hand painting, and he’s getting orders all over the country and things have never been better,” Gillilan said. “He has six people working for him.” “He actually built an enlarger,” Carmalen added. “He was really cutting edge.”

When Robbins realized just how successful Wood was with this photograph of his horse, he filed a lawsuit. “It wouldn’t have been a problem at all if they had signed a contract,” Gillilan said. “But when Desert Dust’s picture got to be a really big deal, that’s when Frank sued.” Wood had already copyrighted the photo and so the judge decided that the two of them would both share the copyright and be able to make colorized photos to sell. As a result, Robbin’s wife started painting her own version of Desert Dust so there are now two different styles of the same photo with two different bylines.

An Investigator Turns Historian

Gillilan always had a fascination with history and making sure all perspectives were told, especially after spending a career keeping people honest in the sin city of Las Vegas. He recalled that as a youngster in 1962, before life led to detective work, he had gone to the Custer Battlefield and heard two completely different stories told by two rangers. Both were right but their stories were wildly different. “That really got to me,” he said. “I learned that there’s more than one story to everything and everybody has their own version of the story.”

As an investigator, Gillilan knew that he would need to know as many versions as possible of a case and look at it from everyone’s point of view. “I also learned along the way that con artists are sharper than a tack in their own little element, although, there’s some really dumb criminals too,” he said.

He used this knowledge to pursue the story of Desert Dust and unravel years of hidden stories to get to the truth of just who this beautiful palomino was. “I think that the families (of Wood and Robbins) respected that,” Carmalen said. “The people directly responsible for Desert Dust and the picture could no longer speak for themselves and the good thing about Gil, he didn’t draw any conclusions. He said, here’s the facts.”

Gillilan ended up with a few unsolved mysteries surrounding Desert Dust and so his investigation continues to this day. One mystery was just who ultimately killed Desert Dust and why. The stallion had been found shot and following the facts he had uncovered, Gillilan concluded it was about fences. “Frank was an opportunist at best,” Gillilan said. “Desert Dust basically got killed because (a rancher named) Franklin let his horses go on somebody else’s land all the time.”

Pursuing A Phantom Horse

During the years of spending his vacations researching Desert Dust, Gillilan met remaining families of Wood and the horse wrangler Frank Robbins. Both families had their own pain, family lore and legends about Desert Dust that slowly Gillilan started to unravel. In the end, he also unintentionally brought about some healing as the families began to see the bigger picture of the legacy left behind by Desert Dust’s capture and brief life.

Gillilan also rekindled old friendships himself and made new, meaningful friends during his investigation into Desert Dust. “It just happened that when I was in high school, there was a young lady a year ahead of me that was editor of the school paper,” he said. “The next year I was the editor of the school paper and we became really close friends. Now she worked at the clerk of the courts office in Rawlins and I called her up.”

His high school friend put together all the information she had about the lawsuit with Desert Dust, helping to put more puzzle pieces together and deepening the mystery surrounding the horse and his picture. He also found out that the real reason Frank sued was not to make more photos himself, although that became a nice benefit. He sued because he wanted to make a movie about his horse with Universal Pictures.

“They said, ‘We don’t want anything to do with something that’s in a legal mess, even if it’s kind of settled,’” Gillian said. “So, they ended up making the movie with Desert Dust, but calling him Pal, short for palomino.” “Fight of the Wild Stallion” was shot as a documentary, recreating the capture of Desert Dust, two years after he had been captured. When Gillilan uncovered a copy of the movie at the American Heritage Center, he felt like he had found gold. Here was Desert Dust, alive and running with the herd.

Another treasure was meeting others who had also been interested in Desert Dust’s story and had interviewed key people before they passed away, including the pilot who had captured Desert Dust with his plane. “They ran them along fences they built into a canyon with the airplane, and the horseback riders would come along on the sides and force them into the box canyon,” Carmalen said. “That plane would scare them and then they closed the canyon behind them.” On one of their family trips to Wyoming, the vacation was to the very canyon Desert Dust was captured in and the family discovered the fences were still there.

Still Searching for New Clues

Gillilan had donated his extensive research to the American Heritage Center and then discovered a Laramie author, Paul W. Papa, who just happened to also be living in Las Vegas. This was the author he knew would be able to tell Desert Dust’s story since, as Gillilan said, he was an investigator but not a good writer. Papa agreed to write Desert Dust’s story but with one stipulation. He said that the real story was how a Las Vegas investigator uncovered the story of this nearly forgotten stallion that at one time represented all of Wyoming’s wild horses.

Gillilan thought that the book, ”Desert Dust”, would be the end of his journey with the palomino. However, he is still drawn to Desert Dust’s story and continues to discover more secrets that were lost to time. “It’s a piece of history that would have been lost,” Carmalen said. “It’s really a fascinating story with a lot of characters that Gill brought to life.”

SOURCE: COWBOYSTATEDAILY.COM