Penguins are flightless, aquatic birds that spend half their lives in water, and on land. They mainly habitat the Southern Hemisphere, with only the Galapagos penguin, north of the equator. They are members of the order Sphenisciformes and family Spheniscidae, and the number of extant penguin species is debated, somewhere between 17 – 20 current living species in total.

They range in size from the Little Blue (or Fairy) Penguin (Eudyptula minor) which stands just 40-centimetres tall to the Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) which averages just over 1-metre tall. Depending on the species, Penguins can weight from as little as 1-kilogram up to 40-kilograms and can live to 20 years. These meat eaters are usually found in coastal waters as well as areas that that are covered in ice.

One misconception about penguins is that they are all cold weather creatures. They are native to the southern hemisphere and are found not just in the Antarctic. Many species inhabit warmer climates with one in particular – the Galapagos Penguin – that calls the region near the Equator home.

Penguins can’t fly, but they sure can swim.

The wings of the Penguin have actually become flippers. This means they are somewhat clumsy on land, but can really move underwater. In fact, they are so agile ducking and weaving about that their actions in water look much like a bird in flight in air.

Penguins are speedy underwater and are deep sea divers.

When a Penguin dives into the water it can reach a speed of up to 12-kilometres per hour and when in high gear, some can reach up to 27 km/h. As for diving, the larger penguins can go deeper, with Emperor Penguins capable of diving down to depths of 565-metres – with dives lasting up to 22-minutes.

The average Penguin spends as much time on land as it does in the water.

Actually, they will spend half of their life in one or the other.

Penguins have devised ways to travel on land that would otherwise be hampered by their overall body shape and length of their legs.

They slide across snow on their bellies in a move known as tobogganing. When upright, Penguins waddle on foot or jump with both feet together in order to navigate terrain.

Although the actual number is not clearly known, there are many Penguin species.

The common belief is that there are between 17 and 20 different Penguin species on the planet.

Penguins use a layer of air for various benefits.

When underwater, the layer of air that is trapped in the smooth plumage of the bird provides buoyancy. The air layer also acts as an insulator when in cold water.

The diet of the Penguin is met with underwater diving.

It may look like they are playing, but since the Penguin feeds on sea life while swimming, it spends a lot of time in the water. One species, the Gentoo Penguin, can make up to 450 dives in a day when foraging for food.

Penguins have special underwater vision.

The eyes of the Penguin have special adaptations which provide superior underwater vision. It assists in finding food and spotting predators.

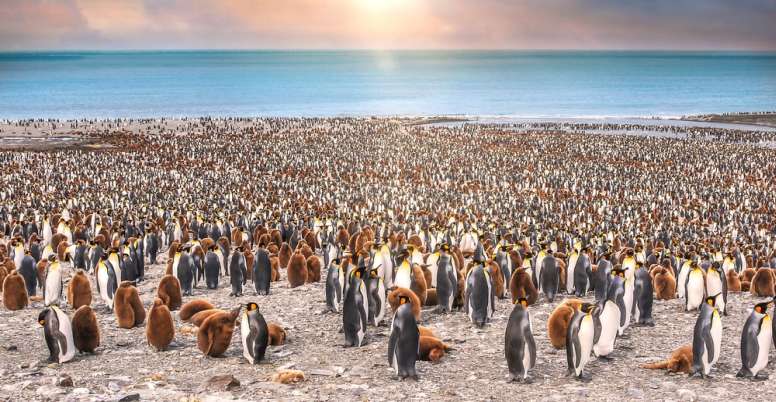

Penguins are highly social.

Because they tend to live in large colonies, Penguins have constant opportunities for social interaction and as a result have a number of vocal and visual signals that they have developed in order to communicate with one another.

They have large extended families.

Penguins also breed in large colonies. The Gentoo Penguin colonies can number just 100 pairs where other species have colonies in the size of several hundreds of thousands.

Penguins know the value of working together.

In harsh environments, Penguins will huddle together to stay warm and conserve energy. Once a bird in the center has warmed up, it moves to the perimeter and this continues so that each Penguin gets a turn in the center of the huddle.

Monogamy is common in the Penguin world.

Pairs will stick together during the breeding season. Often they will re-couple afterwards, or it depends. Sometimes a couple just goes their separate ways after the young have hatched and grow old enough to take care of themselves.

Homosexuality is part of the Penguin culture.

Penguins have the distinction of having the most widely publicized homosexual relationships of the entire animal kingdom.

Penguins have small families.

A typical clutch is two eggs however, the King and Emperor – the largest of the Penguin species – only have a single egg in a clutch. When measured proportionately to the adult Penguin body weight, these birds have the smallest eggs of any bird species on the planet.

Roughly 99.999% of the Penguin species will share the incubation duties.

It’s true, males take on as much of the work as females in the care of the eggs of their young. Well, that is with one exception. The male Emperor Penguin does not participate in this process.

It’s a good thing that most of the male Penguins pitch in with incubation shifts.

When one part of the Penguin couple ventures off to sea in order to feed, the incubating egg is left with the other partner. Sometimes the shift can go days and even months simply because the ice pack can form leaving open ocean as much as 80-kilometres away from the colony.

Penguins have incredible hearing.

It is with their sensitive hearing that parents and chicks are able to locate each other in a crowded colony.

Penguins have a built-in camouflage.

The counter shading of the Penguin plumage – black backs with white fronts – protect these birds from most prey that cannot distinguish a swimming Penguin from sun shimmering on the water surface when viewed from deep in the water below. The dark plumage on their backs helps to ‘hide’ them from above.

They have no land predators.

Penguins are safe in colonies on land as they have no predators except those living in the water. This is very likely why Penguins have little or no fear of humans. Humans have taken advantage of this and have been able to conduct many studies on these interesting birds without much problem.

The size of the Penguin can tell you where they are from.

The larger Penguin species inhabit the colder climates. This obviously means that the smaller Penguin species would live in the warmer climates of the world.

SOURCE: FACT ANIMAL

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/turquoise-meaning-purity-and-happiness-1274380-2-1504aa7dfb854c219b106b2c8848646f.jpg)